I was the Queen o' bonnie France,

And I'm the Sov'reign of Scotland

Robert Burns, Lament of Mary, Queen of Scots

The Auld Alliance

Contents

I. The Stewarts

II. The Cunninghames

III. The Montgomeries and Setons, and Mary, Queen of Scots

IV. The Fullartons

V. The Fergushills

VI. The Earls of Arran

VII. The Earl of Irvine

'Appendix' - Captains of the Scottish Guard 1473 - 1561

The 'Auld Alliance' was an alliance between the kingdoms of Scotland and France which had its origins in the offensive and defensive treaty signed by the Scottish King, John Balliol, and Philip IV of France in October 1295 against their common enemy Edward I of England. The treaty, ratified the following year at Dunfermline, included a provision for the marriage of Edward Balliol, son and heir of King John, and Jeanne de Valois, eldest daughter of Charles, Count of Valois and Anjou, brother of King Philip of France. Balliol was required "to give and assign to the said daughter £1,500 sterling of an annual income for the dowry or gift on account of the wedding" to be drawn from Balliol's lands in France - Bailleul-en-Vimeu, Helicourt, Hornoi and Dampierre in the south of Picardy - as well as those in Scotland - Cunninghame, Lanarkshire, Haddington and Dundee castle.

(image source)

John Balliol had inherited the lands of Cunninghame from his mother, Devorguilla of Galloway. During the reign of King John Balliol the Burgh of Irvine, the 'caput' or capital of Cunninghame, held the status of 'king's burgh'. In 1260 King John's father, John de Balliol, and three other members of the Balliol family were witnesses to an agreement between Godfrey de Ross and the burgesses of Irvine concerning the lands of Armsheugh in the eastern part of Irvine parish. One of these witness was Hugh Balliol who had close connections with the Balliol lands in Picardy.

Sir John de Soulis, one of the four Scottish envoys sent to

France to negotiate the Franco-Scottish alliance, held lands in the district of Cunninghame. In 1293 he appeared before King John at the

Parliament in Scone where he offered homage for a portion of the

lands of Ardrossan. According to the

topographer Timothy Pont the lands of Kilmarnock were also held by

Lord Soulis.

Although the marriage arranged in the treaty of 1295 never took place the Franco-Scottish alliance was frequently renewed and lasted for more than 250 years before formal treaties between Scotland and France were officially ended in 1560. Certain members of the Scottish nobility who fought in France were granted lands and castles as reward for their service. Branches of some of the most distinguished Scottish families, such as the Stewarts, Cunnighames and Montgomeries thus became established in France where they flourished.

Scots and their descendants continued to play a prominent role in the military affairs of France long after the official ending of the Franco-Scottish Alliance in 1560, as General Louis Susane states in his Histoire de la Cavalerie Française (1874) :

From first to last, the Scotch company of men-at-arms affords an unparalleled example in European military annals of a corps lasting uninterruptedly for 360 years without material transformation as to organisation, attributes, and military service. Under the title of Scots Men-at-arms (Gens d'armes Ecossais), one might write the history of the wars waged by France from the days of Joan of Arc to the Revolution.

Part I -The Stewarts

The Scottish company of Men-at-arms - Les Gens d'armes Ecossais - had its origins in the 'Army of Scotland' commanded by Sir John Stewart of Darnley, progenitor of the Stewarts of Aubigny, one of the most illustrious of the Franco-Scottish families to become established in France during the 15th century.

Sir John Stewart of Darnley was the great-grandson of Sir Alan Stewart of Dreghorn, an adherent of Robert the Bruce. In 1315 Sir Alan Stewart was awarded the lands of Dreghorn by King Robert I 'for the service of two archers'. Alan Stewart was a cousin of Walter Stewart, the sixth High Steward of Scotland, whose local power base was Dundonald castle, located a few miles south of Dreghorn. Alan's brother, James, held the lands of Perceton and Warwickhill to the north of Dreghorn. An account of Sir Alan Stewart's life is given in the Genealogical history of the Stewarts, from the earliest period of their authentic history to the present time (1798):

Born towards the end of the Thirteenth Century; served in the wars of King Robert Bruce, to whose interests he was uniformly attached ; received from King Robert a grant of the lands of Dregern, or Dreghorn, in the shire of Air […] In the expedition to Ireland in the year 1315, Alan Stewart, having accompanied Edward Bruce the brother of King Robert, and Thomas Randolph Earl of Moray, who was brother-in-law to Alan Stewart, had his share of military exploits in that kingdom.

It is not known where Sir

Alan Stewart's residence in Dreghorn was located but it was probably

in or near the medieval village of Dreghorn, situated at the

intersection of roads leading from Irvine to Kilmarnock and

Kilwinning to Dundonald via Eglinton. The residence of Alan

Stewart's brother, Sir James Stewart of Perceton, was uncovered

during archaeological

work in 2001.

In 1330 Sir Alan Stewart

of Dreghorn purchased the lands of Crookston and Darnley from Adam de

Glasferth. Alan Stewart and two of his brothers, Sir John Stewart

and Sir James Stewart of Perceton, were killed at the Battle of

Halidon Hill near Berwick-upon-Tweed in 1333. Darnley became the seat

of Sir Alan Stewart's descendants. The 19th century

Scottish historian William Fraser said of Darnley castle:

This old castle of Darnley has long since been removed, but the foundations of it can be traced on an eminence adjoining the present mill of Darnley, and was not more than two miles to the south of Crookston castle, which is about three miles to the south-east of Paisley.

The Stewarts of Darnley

held the lands of Dreghorn until 1520 when they were acquired by the

Montgomery family. Sir Alexander Stewart of Darnley, grandson of Sir

Alan Stewart of Dreghorn, also acquired the lands of Galston in the

Irvine Valley, upon his second marriage to Janet Keith, daughter of

Sir William Keith of Galston. The Keiths of Galston were related to Robert de Keith, Marischal of Scotland, one of the representatives of King Robert the Bruce who negotiated the renewal of the Franco-Scottish alliance at Corbeil in 1326.

Alexander Stewart's eldest son and heir, Sir John Stewart of Darnley, was a commander of the Scottish army sent to aid the Dauphin Charles of France in 1419. The lineage of Sir John Stewart of Darnley is presented in The history of the Stewart or Stuart family (1920) by Henry James Lee:

The second son of Sir John of Bonkyl, was known as Sir Alan Stewart of Dreghorn in Ayrshire. With two other brothers he was killed at Halidon Hill in 1333. He left a son Sir Alexander of Darnley, who died in 1372, whose third son, also Sir Alexander of Darnley, died in 1404, leaving an eldest son, Sir John Stewart of Darnley knighted in 1383 and killed at Orleans, 1429. From him descended the Earls and Dukes of Lennox.

John Stewart's half-brother, William Stewart, also fought in France. Sir William Stewart was descended, on his mother's side, from the Keiths of Galston in Ayrshire.

By 1420 Sir John Stewart of Darnley was made Constable of the Army of Scotland in France, bringing reinforcements the following year. James Grant, author of The Constable of France (1866) states:

The weak and slothful character of Murdoch, Duke of Albany, together with the feuds and quarrels that broke out over all Scotland during his regency, compelled the Earls of Buchan and Wigton, with several other knights, now to return home, leaving Sir John Stewart of Darnley as commander, or, as he was styled, Constable of the Scots in France.

According to William Forbes-Leith, author of The Scots Men-At-Arms and Life-Guards in France (1882), Sir John Stewart of Darnley arrived at the port of La Rochelle “at the head of 4,000 or 5,000 Scots”. This army played a crucial role in enabling the Dauphin to ascend to the throne as King Charles VII of France.

The late medieval chronicler Joannes Ludovicus Micquellus described John Stewart as “a man of a warlike temper, and forward to engage in every hazardous enterprise.” In 1421 he took part in the Battle of Bauge, during which the English army were defeated and Thomas, duke of Clarence, brother of Henry V of England, was killed. Upon hearing of the Scottish victory at Bauge Pope Martin V exclaimed “Truly, the Scots are an antidote to the English!” For his part in the battle John Stewart of Darnley was granted the castle and town of Concressault in Berry. In 1423 he was awarded the lordship of Aubigny-sur-Nere. Of this latter grant, William Forbes-Leith states:

When he conferred upon Sir John Stewart the city and lands of Aubigny, amongst other motives for his generosity, the Dauphin expressly stated that Sir John had almost brought himself to penury by supporting his army out of his own resources.

At the Battle of Cravant the Scots were defeated and Darnley, who had lost an eye in the battle, was taken prisoner. A year later he was freed upon the paying of a ransom by the Dauphin. Upon returning to military service John Stewart led the Scots forces to victory over the English at Mount Saint-Michel.

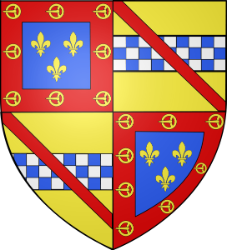

The Battle of Verneuil in 1424 was a disaster for the forces of Charles VII who lost thousands of men, most of them Scots. Despite this setback Sir John Stewart of Darnley and his brother, Sir William Stewart, remained steadfast in their loyalty to Charles. In gratitude the king conferred on John Stewart the county of Evreux in northern France and granted him permission to quarter the fleur-de-lis arms of France with the Stewart arms (pictured below). In 1428 John Stewart returned to Scotland as the ambassador of Charles VII with the aim of raising further troops and negotiating the marriage between Princess Margaret of Scotland and Charles' son Louis.

Sir John Stewart of Darnley, and his younger brother William, were killed at the 'Battle of the Herrings' which took place on the 12th of February 1429 during the siege of Orleans, before the arrival of Joan of Arc. The battle was fought as French and Scottish forces attempted to intercept a supply convoy, which including wagon-loads of salted herrings, headed for the besieging English forces at Orleans. William Forbes-Leith gives a description of the battle in The Scots Men-At-Arms and Life-Guards in France (1882):

The Scots and a great many of the men of Orleans were cut to pieces. John and William Stewart remained dead on the field of battle, one brother having sacrificed his life in endeavouring to rescue the other when wounded and overpowered by the enemy's troops. They were buried in the cathedral church of Orleans in the chapel of Notre Dame Blanche, behind the choir. John Stewart, foreseeing that in the chances of war he might meet his death, had made his will, and had left money for a mass to be said in the above-mentioned chapel every day at the end of matins. Elizabeth Lindsay, widow of Sir John Stewart of Darneley, followed him to the grave at the end of November 1429. She had accompanied her husband from the beginning of the siege. Eight torches given by the city were borne at her funeral.

Sir John Stewart of Darnley was succeeded by his eldest son, Alan, who inherited the lordships of Aubigny and Concressault, while the Lordship of Evreux reverted to the Crown. Alan Stewart held the title of 'Constable of the Scots' and accompanied Charles VII at the siege of Montereau. However, he doesn't appear to have been favoured by the king. In 1437 he resigned his French titles to his younger brother, John, and returned to Scotland.

The Stewarts of Darnley had a long-standing feud with the Boyds of Kilmarnock. In 1439, while in Scotland, Alan Stewart of Darnley was killed by Sir Thomas Boyd of Kilmarnock. Alan's brother, Alexander Stewart, known as 'Bucktooth', pursued Boyd in retaliation and killed him on Craignaught Hill, near Dunlop, Ayrshire.

Sir Alan Stewart of Darnley had two sons, John, who inherited the Darnley estates, and Alexander. Sir John Stewart of Darnley, styled Lord Darnley and Earl of Lennox, married Margaret Montgomery, eldest daughter of Alexander Montgomery of Ardrossan and Eglinton. Lord Darnley held significant tracts of land in Ayrshire, including Dreghorn, Galston and Torbolton. In The Lennox, (Volume 1, Memoirs) William Fraser states:

On 13th May 1450, Sir John Stewart of Darnley granted a charter to his brother, Alexander Stewart, of the lands of Dregairn, for his service, counsel, and assistance often rendered and to be rendered to him; to be held by Alexander and his lawful heirs-male of his won body; whom failing, to return to the granter and his heirs. He also granted to his brother Alexander a charter of the lands of Gallistoun, in the shire of Ayr, which was confirmed by King James the Second , 27th June 1452.

On 17th July 1460, he obtained from that monarch a charter of the lands of Torboltoun, in the shire of Ayr, to be held by him and the lawful heirs-male of his body as a free barony, to be called the barony of Torboltoun. In this charter he is designated John Stewart of Darnley.

[…]

On 20th July [1461], under the designation of John Stewart, Lord Darnley, he obtained from King James the Third, whose father was killed, on 3rd August 1460, at the siege of Roxburgh, a charter of the dominical lands Torboltoun, Drumley, Dregarne, and Ragalhill, in the shire of Ayr, in favour of himself and Margaret Montgomerie, his spouse

In

France, Lord Darnley's uncle, John Stewart, second lord of Aubigny, served as a captain of Scottish forces under Charles VII and Louis XI. John Stewart of Aubigny held the posts of

chamberlain and counsellor to Louis XI and was admitted as a member of the Order of

Saint Michael (Ordre de Saint-Michel) a chivalric order established the king.

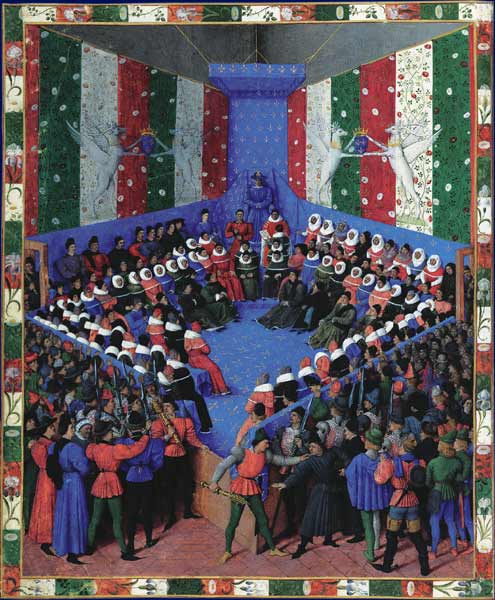

Title page of the statutes of the Order of Saint Michael, drawn by Jean Fouquet, showing king Louis XI presiding over the knights. (image source) John Stewart joined the Order of Saint Michael in 1469, the year of the Order's foundation. In The Nobilities of Europe (1909) he is described as “one of the original Knights of St. Michael”. At the Order's foundation membership was limited to thirty-one knights, later increased to thirty-six including the king.

John

Stewart of Aubigny

married Beatrice, daughter of Berault, Seigneur d'Apchier. Their son

Berault (anglicized as 'Bernard') Stewart, third lord of Aubigny, was

perhaps the most renowned of the Stewarts of Aubigny. The French historian and biographer

Pierre de Bourdeille, seigneur de Brantôme (1540-1614),

described Berault Stewart as a "grand chevalier sans

reproche" (“great knight beyond reproach”).

Berault Stewart was counsellor and chamberlain to the king of France and was made

captain of the Garde Écossaise

in 1493, a post he held until his death in 1508. The

Garde Écossaise or

Scottish

guard was the elite royal bodyguard

composed of Scottish men-at-arms and archers established by Charles

VII in 1425, possibly in commemoration of the Scots who had died at Verneuil a year earlier. At the heart of the Guard were the 24 Gardes de la Manche ('Guards of the Sleeve'), named after their close proximity to the king. Their commander was styled premier homme d'armes de France, the 'first gentleman at arms of France'. To this was added a larger grouping of archers named in the muster rolls as the Archiers de la Garde ('Archers of the Guard').

In 1445 Charles VII organised his forces into fifteen ordnance companies (compagnies d'ordonnance) two of which were composed entirely of Scots. These two Scottish companies were the Scots Men-at-arms (Les Gendarmes Ecossais), which had its roots in the Army of Scotland commanded by Sir John Stewart of Darnley; and the Royal Lifeguards (Compagnie Ecossaise, de la garde du Corps du Roi), also known as the Scots Lifeguards or Scottish Guard. When Berault Stewart became captain of the Guard in 1493 there were there were 25 Gardes de la Manche and 78 Archiers de la Garde.

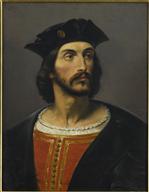

Contemporary portrait of Berault Stewart on a bronze medal by Niccolo Spinelli of Florence, from the frontispiece of Some account of the Stuarts of Aubigny, in France (1891) by Elizabeth Cust. He is depicted wearing the collar of the Order of Saint Michael. The collar of the Order was made from shells, the badge of the pilgrim. Many commanders of the Scottish Guard were also members of the Order of Saint Michael.

Berault

Stewart's heraldic device, which he wore on his surcoat and standard,

was the red lion of Scotland on a plain background strewn with

buckles. According to Historic Devices, Badges and War-Cries

by Bury Palliser this signified "that he was the means of holding

united the Kings of Scotland and France against England." His

motto was Distantia jungit, “It unites the distant”.

Berault Stewart took part in the Italian Wars where he was made Viceroy of Naples and Calabria. For his part in the victory in 1505 over the Spanish forces at Terranuova he was made Duke of Terranuova and Marquis of Girace. In 1503 Berault set about writing a book on the art and conduct of warfare entitled A book and treatise to understand what measures a prince or commander must take to conquer a country or pass through or cross the country of his enemies, composed by Berault Stewart.

Although he was born and raised in France, Berault Stewart considered Scotland his native country. In the role of ambassador he made four trips to his ancestral homeland. Part of his treatise on warfare is said to have been dictated to his chaplain, Etienne le Jeune of Aubigny, during his final trip to Scotland in 1508. During this visit a tournament was staged in honour of the French guests. Berault Stewart was made judge of the tournament and hailed as "the Father of War" by king James IV. Arrangements were made for Berault Stewart to accompany the king on pilgrimage to Whithorn. James IV had made a pilgrimage to Whithorn every year since 1491 and made stops at Kilwinning abbey and Irvine during his pilgrimages of 1506 and 1507. However the planned pilgrimage of James IV and the Lord of Aubigny never took place. Berault Stewart fell ill and died at Corstorphine, near Edinburgh, on the 11th of June 1508. He was buried at the Blackfriars church in Edinburgh and his heart taken to the shrine of Saint Ninian at Whithorn, as stipulated in the will Berault made a few days before his death.

After the death of Berault Stewart the lands of Aubigny passed to Berault's nephew, Robert Stewart, son of the aforementioned Sir John Stewart of Darnley, Earl of Lennox. Two other sons of Lord Darnley served in France – William Stewart, styled Seigneur d'Oizon and de Grey, and John Stewart of Henriestoun. All three brothers had served under Berault Stewart. John Stewart of Oizon was captain of the Scottish Guard from 1508 to 1512 when he was succeeded by Robert Stewart of Aubigny. When Francis I ascended to the throne in 1515 he made Robert Stewart a Marshal of France, and he remained captain of the Scottish Guard until his death in 1542.

Robert Stewart (c. 1470 - 1544), fourth lord of Aubigny, captain of the Scottish Guard and one of the four Marshalls of France.

The Château de La Verrerie, located a few miles from Aubigny, was built by Berault Stewart and his nephew and successor Robert. Photograph by Dmitry Gurtovoy. (source)

Scottish Guards of Francis I in ceremonial dress, from Les Monuments de la Monarchie Francaise (1729–1733) by Bernard de Montfaucon. The guard on the left is depicted wearing a jacket emblazoned with the crown and salamander emblem of Francis I. Forbes-Leith gives a description of the Guards, captained by Robert Stewart of Aubigny, at the crowning ceremony of Francis I:

At the entry of Francis I. into Paris in 1515, the 24 Scots Life-guards who figured in the ceremony were all on foot carrying halberds. They wore white cloth jackets covered with gold embroidery, white hose, and sallets with white plumes. Their captain, Stewart d'Aubigny, marched at their head, accoutred with a jacket of white cloth with the salamander embroidered before and behind, surmounted by a great crown of silver-gilt.

Among the names of the 25 senior Gardes de la Manche recorded in the muster roll of 1515 is 'Patrix Conighan' or Patrick Cunninghame. A kinsman, Andrew Cunninghame, served in the Archers de la Garde.

Part II - The Cunninghames

The Cunninghames family feature prominently in the history of the Auld Alliance. The Cunninghames took their name from the district of Cunninghame in Ayrshire, as James Paterson states in History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton :

It is unquestionable that the district was known by the name of Cunigham, or Cuninghame, long before the adoption of patronymics in this country – consequently the family derived their name from the district, and not the district from the family.

The district of Cunninghame is said to derive its name from either the Celtic Cuinneag, meaning a milk-pail or churn, or the British Cuning, meaning a rabbit or 'coney'. In Civilisation in Scotland (1882) the French historian and philologist Francisque Michel states, "The rabbit had a name according to its age, -either cuning, cunyng, kinnin [...] Cuningar, cunningaire, means a warren."

The Cunninghame family established one of their chief seats at Kilmaurs which, according to Paterson, was known from antiquity as “the township of Cuninghame”, an ancient stronghold of the district. The family also established seats at Glengarnock, Auchenharvie, Aiket, Kerelaw and Cunninghamehead. The latter estate was originally called Woodhead, renamed as Cunninghamehead after the family name.

Cunninghames

were present in France from the early 15th century. When

Sir William Douglas arrived in France in May 1419 he was accompanied

by Thomas Cunninghame who “commanded a body of men-at-arms and

archers”. Sir Henry Cunninghame, son of Sir William Cunninghame of

Kilmaurs, was among the second contingent of Scottish troops

despatched to France in 1420. The following year, at the Battle of

Bauge, Lord Fitzwalter was taken prisoner by a certain Henry

Cunninghame. Sir William Cunninghame was one of the Scots slain at

the Battle of Crevant in 1423. These are just some of the many

members of the Cunninghame family who fought and lived in France

during the 15th century. The surnames of 386

Scottish soldiers serving in France in 1475 have been identified. Of

these, according to Grant G. Simpson, author of The

Scottish Soldier Abroad, the Cunninghames

were the most numerous.

Three of the most notable members of the Cunninghame family in France were Robert Cunningham and his sons, Joachim and John. Robert Cunningham, who was an esquire of the king's stable and a royal counsellor and chamberlain, acquired the lorship of Villeneuve and Cherveux. He had an imposing castle constructed near Niort, in the heart of Cherveux. Robert Cunninghame's eldest son, Joachim, was lord of la Roche, while his second son, John, held the lordship of Cange and la Motte-Freseau, in Anjou. John Cunningham, who was also a counsellor and chamberlain to the king of France, rebuilt the Château de Cange and paid for the reconstruction and endowment of the neighbouring parish church of St. Avertin.

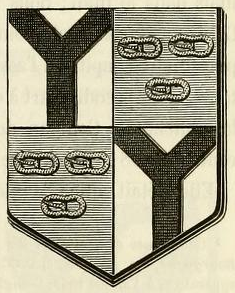

The arms of Saint Avertin display the 'pairle' or 'shakefork' device of the Cunninghames. (image source)

The

arms of the Cunninghames in France - a shakefork with three gold

clasps. The family of Joachim Cunningham replaced the clasps with

three fleur-de-lis. (image source: Les Ecossais en France by Michel Francisque)

In 1446 Robert Cunninghame was captain of the ordnance and in charge of 40 men-at-arms and 80 archers. Three years later he commanded the Scottish forces at the siege of Rouen.

At the siege of Caen in 1450 Robin Campbell, a lieutenant of Robert Cunningham, and three other Scots, William Cunninghame, Robert Johnston and James Haliburton were involved in a plot with the English. The plot was discovered and Robin Campbell was brought to trial where he was declared guilty of high treason and executed. Campbell's commanding officer, Robert Cunninghame, was also accused of involvement in the plot. William Forbes-Leith gives an interesting account of the case in The Scots Men-At-Arms and Life-Guards in France (1882):

Robert Cunningham was in his turn brought to trial. He belonged to one of the best families in Scotland, and King James exerted himself in his favour, as also in behalf of the other accused. His letter to the King of France is still preserved. After many compliments James continues, that he has been informed of the arrest of Robert Cunningham for treason, but for his own part he can only consider this arrest as due to the wicked and calumnious accusations of jealous enemies. If the accused is really guilty, James does not wish to excuse his crime; if, on the contrary, and the ever loyal conduct of his ancestors would give weight to the supposition, Cunningham is the victim at this moment of an infamous calumny, he begs that he may be permitted to defend himself against his enemies and rivals, and that, considering the alliance of the two kingdoms, he may have the benefit of the French laws, and defend himself by duel or by any other legitimate means. If his innocence is proved, let him know how much he is beholden to the prayers of the King of Scotland and the King of France […] This letter is dated at Stirling, April 15th, and signed by the king.

The letter was accompanied by a petition addressed to the king of France signed by a dozen Scottish nobles, presented by Archibald Cunninghame, brother of the accused Robert Cunninghame. The signature contains the names of a number of Ayrshire lords including Alan, lord of Monkredding in Kilwinning, Alexander Cunninghame of Kilmaurs, Robert Boyd, lord Boyd of Kilmarnock, Robert Cunninghame of Auchenharvie and John Kennedy of Blairquhan. Alan, Lord Cathcart and John Ross of Hawkhead, both holders of estates in Renfrewshire, also appear to have been signatories. Forbes-Leith states:

The signers set forth in this petition the great services rendered by the accused both to Scotland and to France, and that the persecutions suffered by Robert were evidently the result of calumnious denunciations. This petition concludes in the manner of the times by a challenge in the name of the Scotch nobility, all the signers undertaking in turn to sustain in personal combat the honour of Robert Cunningham. Their twelve seals are attached as a pledge of their faith. This also bears date the 15th of April. Other petitions were addressed to the statesmen of the king, and Robert Cunningham regained his liberty.

[…]

In his account of the Scots Guard, Le Pipre de Neuville ascribes to envy and jealousy the persecution suffered by Robert Cunningham; and the king's herald, Berry, a contemporary writer, after mentioning him as present at the siege of Caen, adds that “during the whole of the war in Normandy, Robert Cunningham behaved nobly, most bravely and most honourably.”

The accusations of treason don't appear to have hindered Robert Cunninghame's military career. Between 1461 and 1464 he commanded 50 lances fournies. This increased to a company of one hundred lances fournies between 1465 and 1472. Robert Cunninghame's lieutenant was a kinsman, Graham Cunninghame. In 1469 twelve Cunninghames (besides Robert and Joachim) were serving either in Robert Cunninghame's company of ordnance or in the Scottish Guard. Berault Stewart, future captain of the Scottish Guard, served as a man-at-arms under Robert Cunninghame from 1469.

The Cunninghames played a particularly prominent role in the Scottish Guard. Archibald Cunninghame appears to have been the first of the family to join the Guard. He is recorded as a man-at-arms in the King's Bodyguard in 1449-50. The French chronicler Mathieu d'Escouchy (1420-1482) describes the Scottish Guard who accompanied Charles VII at the entry into Rouen in 1449:

In the first rank were the archers and crossbowmen of the king's bodyguard to the number of five or six score, more gorgeously clad than the rest. They were all clad in jackets without sleeves, of the colour of red, white, and green, covered with gold embroidery, with plumes in their helms of the same colours, and their swords and leg armour richly coated with silver.

There was at least one Cunninghame in the Guard every year during the periods 1465-1548, 1552-1564 and 1567-1571 (William Forbes-Leith notes that "the Muster Rolls for 1565 and 1566 are missing"), with the name appearing in the muster rolls under a variety of spellings including Coningham, Conigham, Conighan and Conighain. For almost twenty years the captaincy of the Guard was held by a Cunninghame. In 1473 Robert Cunninghame was made Captain, a post he held until 1478. On assuming the captaincy of the Guard he ceded his company of ordnance to his son Joachim. Robert was succeeded as Captain of the Guard by his younger son, John, who held the post until 1492. A kinsman, David Cunningham, served as attendant man-at-arms to the captain from 1487 to 1492. In The Scots Men-At-Arms and Life-Guards in France (1882) William Forbes-Leith gives a description of the costume of the Scots Guards during the captaincy of John Cunninghame:

In 1487, the Captain of the Scots Guard was John Cunningham. The jacket which he bore over his armour was composed in front of crimson damask lined with black satin, and behind of buckram. He also wore a short cloak. His jacket was embroidered with two great crowns, one in front and one behind, encircled with wreaths of roses and rose branches. The whole was studded with golden and silver spangles and tassels. John Cunningham bore on his helmet “a plume of eighteen feathers, in the form of a bird's crest, of the king's colours, which were red, white, and green. These plumes were adorned with gold braid and pendant ornaments in gold.” This costume was given to the Captain of the Scots Guards in April, 1487. The archers of this guard bore jackets without sleeves, made of stripes of crimson, green, and white, and embroidered collars of white and yellow. They carried a bow, and on the shoulder a quiver full of arrows barbed and feathered.

After Robert Cunninghame was made Captain in 1473 the number of Cunninghames in the Guard steadily increased until 1491-92, the last two years of John Cunninhame's captaincy, when there were no fewer than fifteen Cunninghames in the Guard which had a total of 106 personnel.

Adoration of the Magi by Jean Fouquet (1420-1481) (image source) Painted sometime between 1452 and 1461, the Adoration of the Magi depicts Charles VII as one of the three Magi attended by his Scottish Guard. The scene in the background may be a representation of a mock battle held as part of the Twelfth Night or Epiphany celebrations.

When Robert Cunninghame died in 1479, his eldest son, Joachim, inherited the lordship of Cherveux. Joachim Cunningham married Catherine de Montberon. Their son, Jacques (James), was in turn lord of Cherveux and a royal master of household and captain of Niort under Louis XII and Francis I.

Joachim Cunninghame died of wounds received at the siege of Novare. His brother, John Cunninghame, died in Piedmont from injuries sustained during the Italian campaign of Charles VIII.

Other notable members of the Cunninghame family in France include Peter Cunninghame, one of the Scottish members of the royal bodyguard known as Les Cent Gentilshommes. A description of this guard is given by William Forbes-Leith:

On the 4th of September, 1474, Louis XI. formed a new company of 100 guardsmen, to which none were admitted save such as were well-tried soldiers, and could furnish undeniable proof of good descent. [...] Their duties were to guard the king's person - an honour which they divided with the Scots Guards. These marched immediately before the king, and the Cent Gentilshommes immediately after, so that he was surrounded by the two guards.

In Chapter 8 of The Scots Men-At-Arms and Life-Guards in France, which covers the reign of Francis I (1515-1547), Forbes-Leith mentions "Peter and James Cunningham, Lord of Cange" as being among those "close to the king's person and in high favour at court".

A certain member of the Cunningham family acquired the lands of Arcenay, in Burgundy, by marriage to the heiress, Martha of Louvois. According to John Hill Burton, author of The Scot Abroad (1864), the family can be “traced through many distinguished members to the first Revolution, when it disappears; but it reappeared, it seems, in 1814, and is supposed still to exist.” William Forbes-Leith describes one member of this family, Guy de Cunningham, as “an officer of high reputation, who served France sixty years, and distinguished himself in 1734, when lieutenant-colonel of the Regiment Dauphin, in an affair in Italy, in which he undertook to cover the retreat of the army by charging the enemy with 400 picked men, and escaped without a wound. For that gallant deed he received the cross of Saint Louis, a pension of 1200 livres, and was made colonel of the regiment of Flanders, with the rank of brigadier. He died in 1746, and was interred in the chapel of Arcenay by the side of six of his ancestors.”

Walter Scott's historical novel Quentin Durward (1823) tells the story of a young Scottish archer from the Borders who joins the ranks of the Scottish Guard of King Louis XI. The story features a guardsman named Archie Cunningham among the representatives of Scottish families. Scott's novel proved popular in France where it galvanised interest in Scotland and the Auld Alliance.

Part III - The Montgomeries and Setons, and Mary, Queen of Scots

John Montgomery, younger son of Alexander Montgomery of Ardrossan and Eglinton, was one of the Scottish captains who served in France during the 15th century. John Montgomery appears to have held the barony of Giffen in the parish of Beith in Ayrshire, as he was designated John Montgomery of Giffen in a proclamation at Irvine. He was described by William Forbes-Leith as “one of the most renowned leaders not only of the Scots, but of the whole French army”. He accompanied Alan Stewart, Constable of the Scottish army in France, at the siege of Montereau and was one of the “distinguished Scotch captains” present at the siege of Meaux in 1439. He was awarded the lordship of Azay for his service in France.

In 1444 John Montgomery led the Scottish forces of Charles VII during the campaign against the Swiss. In October of that year the Scottish troops took the city of Dambach where they established their winter quarters. Suffering from a lack of provisions the Scottish contingent at Dambach were forced to plunder the surrounding countryside where they met stiff resistance from the local population. It was during one of these raids that John Montgomery lost his life. On the death of John Montgomery Forbes-Leith states:

His body was transported to Dambach by his countrymen, put into a mixture of wine and oil, and sent to Scotland.

John Montgomery's remains may have been returned to Giffen where there was a chapel and burial ground. This chapel, dedicated to St Bridget, is said to have belonged to Kilwinning abbey.

Drawing of Giffen castle from James Paterson's History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. (image source)

John Montgomery was the

ancestor of the Montgomeries of Lorges. James Montgomery of Lorges

was one of the Scottish commanders who, in the words of William

Forbes-Leith, “maintained the reputation of the Scottish arms”

during the Italian campaign of 1515. He is said to have purchased

the county of Montgomery in Normandy, the ancestral homeland of the

Scottish Montgomery family, from which he derived the title Count of

Montgomery.

James Montgomery accidentally wounded King Francis I during a mock battle staged as part of the Twelfth Night celebrations in 1520. Forbes-Leith, in his description of the Adoration of the Magi by Jean Fouquet, recounts how during "the Twelfth Night amusements of the French Court... moderation originally intended was not unfrequently overstepped" and gives the following description of the "courtly revels" of Francis I:

Having heard that in the house of the Comte de Saint-Pol a king had been chosen on Twelfth Night, he sent a herald to defy the newly-proclaimed monarch, and, accompanied by a troop of youthful courtiers, assaulted the mansion. Both the besiegers and besieged fought with snowballs, eggs, and apples. A great quantity of snow had fallen recently, and the assailants had plenty of ammunition; but it was not so with the beleaguered party. When they had expended their supply of missiles, and the besiegers were forcing an entrance, an impudent champion threw out of a window a burning log, which lighted on the king's head, and wounded him so dangerously that for several days his medical attendants almost despaired of saving his life, though the gallant prince would never allow inquiry to be made respecting the unlucky culprit, saying that it was partly his own fault, and he must put up with the consequences. [...] The ill-starred combatant was no other than James Montgomery, Seigneur de Lorges

In 1543 James Montgomery succeeded John Stewart of Aubigny as captain of the Scottish Guard. For the next eighteen years the Scottish Guard was captained by a Montgomery, either James Montgomery, or his son, Gabriel. This period is described by Stephen Wood, author of The Auld Alliance, Scotland and France: The Military Connection, as a Montgomery "monopoly" of the Guard comparable to that previously held by the Stewarts of Aubigny. James Montgomery was captain from 1543 to 1556. From 1547 Gabriel Montgomery served as senior homme d'armes (man-at-arms) then Lieutenant to his father, prior to his elevation to the captaincy in 1557. James Montgomery resumed the captaincy of the Guard in 1559. Two kinsmen, François Montgomery and James Montgomery of Corbuzon, appear in the muster rolls as the captain's attendant homme d'armes. From 1559 until his leaving the Guard in 1564, James Montgomery of Corbuzon was styled premier homme d'armes, the title held by the commander of the Gardes de la Manche, the 'Guards of the Sleeve'. According to William Forbes-Leith, “in the principal royal ceremonies, such as the coronation of the kings, their entry into the towns, and their burials, the “Gardes de la Manche” always appeared conspicuous, and occupied the most prominent places.”

Three members of the Montgomery family are among the Scottish names recorded in the few surviving Muster Rolls of the Cent Gentilshommes, the company of 100 guards established by Louis XI in 1474.

In 1548

the Scottish Guard escorted the six year old Mary Stewart, Queen of

Scots, on her journey to France. Mary and her entourage sailed from Dumbarton to Brittany before being escorted to Saint-Denis, on the outskirts of Paris. In France Mary was attended by her own court

including the 'Four Marys' - Mary Seton, Mary Livingstone, Mary Fleming and Mary Beaton - four daughters of Scottish noble families

chosen by Mary Stewart's mother, Mary of Guise. Ten years after leaving Scotland Mary, Queen of Scots was married to the Dauphin

Francis, son and heir of king Henry II of France. As

part of the strengthened alliance with Scotland, Henry II extended the privileges of the Scottish Guard. According to William

Forbes-Leith this was done “with a view to gain partisans in

Scotland”.

Gabriel Montgomery (1530 - 1574) (source)

As captain of the Scottish Guard Gabriel Montgomery became infamous as the knight who mortally wounded King Henri II of France during a jousting tournament when a splinter from Montgomery's lance broke off and pierced the king's eye. There is an account of this event in the Preface to the Calendar of State Papers Foreign, Elizabeth, Volume 2: 1559-1560 (1865):

Two

independent accounts of this event, each drawn up by an eye-witness,

have come down to us; one from the report of the English Ambassador,

the other incorporated into his Memoires by Villeville. These two

narratives agree so closely with each other that they admit of being

woven into one continuous and consistent narrative. From their united

testimony it appears that the King entered the lists upon the

afternoon of June 29, and was armed by Villeville. As one of the

defendants, Henry was required by the laws of the game to run three

courses, and three courses only; and then was expected to resign his

place to the next comer on the same side. He accordingly ran the

first course with the Duke of Savoy and the second with the Duke of

Guise, on both of which occasions he acquitted himself with his usual

skill, and gained his usual amount of applause. His third antagonist

was the Count of Montgomery, the son of the Count De Lorges, one of

the captains of the Scottish Guard, "a tall and powerful young

man." He struck Henry so roughly with his lance that the King

reeled in his saddle, and nearly lost one of his stirrups. It was now

M. De Villeville's turn, and he presented himself at the barrier for

the purpose of entering the lists, but the King interposed, saying

that he himself wished to try another course with his late

antagonist, the issue of the previous encounter having been too

indefinite to be satisfactory. Observing that he was irritated and

excited, all present endeavoured to dissuade him, but in vain. He

charged Montgomery upon his allegiance to remount and to take his

place at the other end of the lists. There was no alternative, and

Montgomery obeyed with marked reluctance. Both of the antagonists

splintered their lances successfully; but the Count neglected to

throw away the broken shaft which remained in his hand. It struck the

King's helmet as the horses passed each other in the lists, forced

open his visor, and (according to Throckmorton's narrative) "hitting

his face, gave him such a counterbuff as drove a splinter into his

head right over his eye on the right side; the force of which stroke

was so vehement, and the pain was so great, that he was much

astonished." He dropped the rein, bent forward over his horse's

neck, and had much ado to keep himself from falling. He was lifted

from his horse and unarmed close by where the English Ambassador was

seated, who consequently had a near view of the whole occurrence. The

hurt seemed not to be great, but the King was very weak, and had the

sense of all his limbs almost benumbed, "for being carried away

as he lay along, nothing covered but his face, he moved neither hand

nor foot, but lay like one amazed." […]

The most expert surgeons in France were at once summoned, but they

were unable to extract the splinters of wood which they had reason to

believe remained deep in the wound. […]

The doctors in attendance busied themselves in dissecting the heads

of four or five criminals, whom they caused to be executed in the

meantime, and on which they had inflicted injuries similar to that

which had befallen the King. All, however, was in vain. Henry had

declared from the first that he had received his death-blow. After

lingering through more than a week of agony he became insensible, and

on the 10th of July death ended his sufferings.

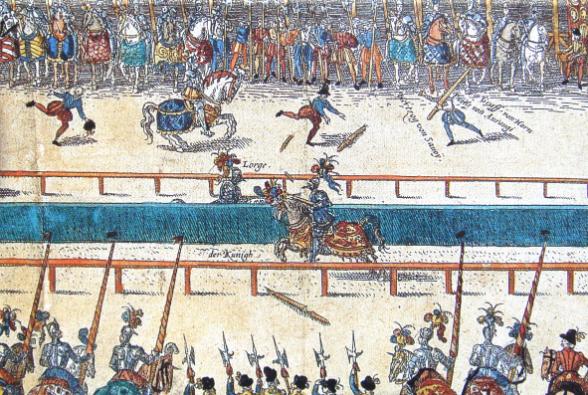

Anonymous 16th century German print showing the fatal joust between

King Henry II and Gabriel Montgomery of Lorges. (source)

The French astrologer Michel de Nostredame (1503-1566), better known as Nostradamus, reputedly predicted the death of Henry II in one of his quatrains:

The

young lion shall overcome the older one,

on

the field of combat in single battle,

He

shall pierce his eyes in a golden cage,

Two

forces one, then he shall die a cruel death.

Illustration showing Henry II on his deathbed attended by, among others, Mary Queen of Scots and her husband Francis. (source)

While no proceedings were taken against Gabriel Montgomery for his role in the king's death, he felt it necessary to retire to his estates in Normandy, where he studied theology. His father, James Montgomery, died in 1561 at an advanced age, between eighty and ninety years old. Gabriel Montgomery converted to Protestantism and became a leader of the Huguenots. After surviving the St Bartholomew's Day massacre in 1572 he fled to England. He returned to France the following year with the intent of relieving the Siege of La Rochelle. Gabriel Montgomery of Lorges was captured in Normandy and executed on the 26th of June 1574.

A short account of the Montgomeries of Lorges by Professor Le Herricher of the College of Avranches is quoted in A genealogical history of the Montgomerys and their descendants (1903) :

Alexander de Montgomery, lord of Ardrossan and Eglintoun, was cousin of James I., King of Scotland. From this nobleman descended Robert de Montgomery, father of Jacques (James), who was celebrated under the name of 'captaine de Lorges.' […] His son Gabriel I., who became the 'great' Montgomery, and who was the person who mortally wounded King Henry II., succeeded to the estates of his five brothers and sisters. He married Isabeau de Teral, lady of Lucey, and through her became seigneur of Lucy, and of several parishes in Avranchin, in Normandy. The family chateau (still known as the chateau de Montgomery, but now unoccupied and going to ruin) is situated at Lucey, about three leagues from the town of Avranches. The present building is, however, comparatively modern, having been built about the year 1620, by Gabriel II., son of the great Montgomery. The ancient castle of the family stood at a short distance from it, on a cliff overlooking the river Lelune.

Henry II of France was succeeded by his fifteen-year old son, Francis II, who was married to Mary Stewart, Queen of Scots. Francis II reigned for 18 months until his death in December 1560. When Mary, Queen of Scots, returned to Scotland the following summer she was accompanied by Hugh Montgomery, third Earl of Eglinton. The Earl of Eglinton was, in the words of Sir William Fraser, “one of Mary's most steadfast adherents during the troublous and eventful period which immediately followed her arrival in Scotland”.

During her tour of south-west Scotland in August 1563 the twenty-year old Mary, Queen of Scots stayed at Eglinton castle before travelling to Ayr, probably via Irvine. According to local tradition she stopped at Seagate castle in Irvine, which belonged to the Earl of Eglinton. While this may be true there is no evidence to support it. The current Marymass Fair, involving the Marymass Queen, representing Mary, Queen of Scots, and her Four Maries, is a modern adaption of a medieval church fair, the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary.

Portrait of Mary, Queen of Scots (c.1559) by François Clouet, court painter of the French royal family. (source)

I was the Queen o' bonnie France

And I'm the Sov'reign of Scotland

Eglinton castle, where Mary, Queen of Scots stayed on August 1st-2nd 1563. (image source)

Margaret Montgomery, eldest daughter of the third Earl of Eglinton, married Robert Seton, eighth Lord Seton, who was made Earl of Winton in 1600. Their third son, Sir Alexander Seton of Foulstruther, became Earl of Eglinton after the fifth Earl of Eglinton, Hugh Montgomery, died childless in 1612. Sir Alexander Seton took the name Montgomerie and the titles Lord Montgomerie and Earl of Eglinton. In Memorials of the Montgomeries, Earls of Eglinton (1859) Sir William Fraser states:

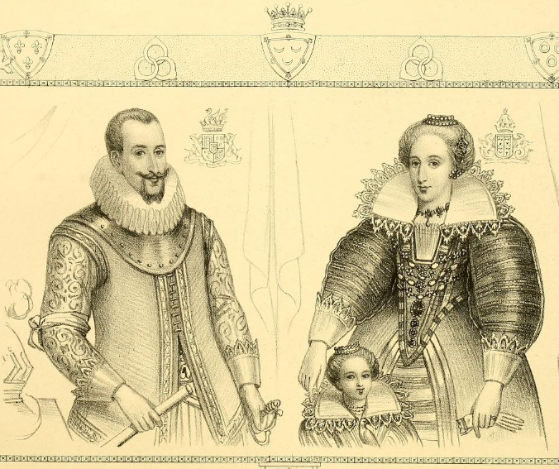

According to an arrangement between the families of Eglinton and Winton, it was agreed that the third son of the Countess of Winton, who was the nearest heir of Hugh, fifth Earl of Eglinton, should be his successor in the earldom. In pursuance of this arrangement, there was obtained on 28th November 1611, a Crown charter of resignation and novodamus in favour of this Earl, whom failing, to Sir Alexander Seytoun of Foulstruther, Knight, son of Lady Margaret Montgomerie, Countess of Wintoun, and others, and the heirs-male to be born to them respectively, of the lordship and barony of Kilwinning, and lordship and earldom of Eglinton, which are thereby of new united, erected, created and incorporated into one whole and free earldom, to be called the Earldom of Eglintoun. The sanction of the Crown was thus obtained to the transference of the earldom of Eglintoun to the Seton family on the death of the fifth Earl.

Robert, first Earl of Winton and his wife Margaret Montgomery, Countess of Winton, with their daughter Isabella, future Countess of Perth. Illustration from Memorials of the Montgomeries, Earls of Eglinton by Sir William Fraser.

Sir Alexander Seton appears to have been residing in or travelling through France when he was notified of his claim to the Earldom of Eglinton. In The History of the House of Seytoun (1829), Sir Richard Maitland states:

This Alexander earle of Eglingtone was sent for out of France by his uncle, the earle of Eglintone, who, having noe heirs of his own body to succeed to the Earledome of Eglingtone, disponed his estate freely to this Sir Alexander Seton

The Setons had long-standing connections with France and the Auld Alliance. In 1419 Sir Thomas Seton and his brother each commanded a company of men-at-arms and archers. According to William Forbes-Leith the Seton brothers were “conspicuous amongst the most faithful followers of the Dauphin. Thomas was favoured with the estate of Langeais, and appointed to accompany Charles wherever he went.” Thomas Seton was captain of twenty seven men-at-arms and a hundred mounted archers and was employed as bodyguard to the Dauphin Charles, six years before the founding of the Scottish Guard. Seton's company of 127 men-at-arms and archers can perhaps be viewed as a precursor or progenitor of the Scottish Guard. Thomas Seton was among the many Scots killed during the Battle of Cravant in 1423. Sir William Seton, the eldest son of Sir John Seton, 2nd Lord Seton, also fought for Charles VII, dying at the Battle of Verneuil in 1424. In The History of the House of Seytoun by Sir Richard Maitland there is a mention of Robert Seton, second son of George, fourth Lord Seton, described as “ane man of armes in France” who died at the Castle of Milan. Robert Seton's son, William, is also described as “ane man of armes in France” and his name appears in the 1558 muster roll of the Scottish Men-at-arms as detailed by William Forbes-Leith.

Francisque-Michel in his work Les Ecossais en France (1862) mentions Graham Seton as an archer in the Scottish Guard about 1467 and George Seton as member of the Guard in 1575. Four Setons are listed in the Guard's muster roll for 1587 and three members of the family are recorded in the roll of 1624.

Sir John Seton of Cariston, a cousin of the Earl of Eglinton, had three sons, two of whom travelled to France. His second son, also called Sir John Seton, is described as “Captain in the Scots Guards in France, married to a daughter of the Count of Bourbon” in George Seton's History of the Family of Seton During Eight Centuries (1896).

Another member of the family and namesake, Sir John Seton, was Lieutenant of the Guard from 1632 to 1640. He is presumed to have been the son of the aforementioned John Seton, Captain of the Guard. By the early 17th century the Scottish Guard had ceased to be an exclusively Scottish company, with Frenchmen making up two thirds of the personnel. In a letter to the Marquis of Hamilton dated 3rd of November 1634 he describes himself as “the last Scots Lieutenant” of the Guard. Rivalries between the Scots and the French came to the fore during this period as William Forbes-Leith recounts in Chapter 11 of The Scots Men-at-arms and Life-guards in France, entitled 'The Last Kings of France – The Last Scots Guards':

Louis XIV. maintained the companies of Scots Men-at-arms and Scots Guards, the only two corps in the French army which had survived the troubles of the sixteenth century, and allowed both companies to remain in possession of their privileges. One of them was to take precedence of the whole French army in virtue of seniority – a most precious privilege […] It was natural that the French should murmur at the distinctions bestowed on the strangers, and the records of the court prove that they frequently met with jealous opposition.

At the funeral of Louis XIII., according to the ceremonial, the Scots Guards were to accompany the corpse from St Germain's to St Denis, and not to leave it till it was deposited in the Bourbon vault. When the corpse reached St Denis, at the church door a disputed point arose regarding the pall between the Scots Guards and the royal footmen who had taken hold of it. The Guards claimed their privileges, and Lieutenant Seton defended their claim in opposition to the Prior, who was in favour of the royal servants. The point was then referred to the Marquis de Sainctot, Master of Ceremonies, who decided in favour of the Guards ; however Lieutenant Seton gave ten pistoles [gold coins] to the royal servants. The corpse was then borne to the midst of the choir by eight Scots Guards.

In 1679 a certain David Seton is recorded as Brigadier of the Guard. The surname Winton appears in the muster rolls of the Guard. In Scotland this name derives from the lands of Winton in Pencaitland, East Lothian, held by the Seton family since the 12th century.

The sixth Earl of Eglinton's father, Robert Seton, Earl of Winton, and grandfather, George Seton, both had strong ties to France. George Seton spent his childhood in France where he was educated. His epitaph at Seton Collegiate Church states:

Being deprived of his most worthy father, when he was a young man, living in France, he returned home, and in a short time afterwards, by a decree of the Estates of the Kingdom, he is sent back to France, and there, as one of the Ambassadors, he negotiated and ratified the marriage between Queen Mary and Francis, Dauphin of France, and the ancient treaties between the French and the Scots.

George Seton married Isabel, daughter and heiress of Sir William Hamilton of Sanquhar, by which he acquired the Manor of Sorn and lands in Kyle in Ayrshire. In 1583 he returned to France as ambassador with the intention of continuing the Auld Alliance. He was accompanied by his sons Robert Seton, future Earl of Winton, who had been educated in France, and Alexander Seton, future Earl of Dunfermline. While in France Lord Seton made efforts to secure the position of Captain of the Scottish Guards for one of his sons. Around this time George Seton's sister, Mary Seton, one of the 'Four Marys' who attended Mary, Queen of Scots, retired to the Convent of Saint-Pierre in Rheims, northern France. Mary Seton spent the remainder of her life at this convent which was headed by Renée of Lorraine, sister of Mary of Guise and aunt of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Portrait of George, 7th Lord Seton, and his family, including, second from left, Robert Seton, future Earl of Winton and father of the Earl of Eglinton. The youngest of the sons is William Seton, who later acquired the lands of Kylesmuir in the parish of Mauchline, Ayrshire. Sir Walter Scott described this family portrait of the Setons as a “very curious portrait... painted in a hard, but most characteristic style by Sir Antonio More. The group slope from each other like the steps of a stair, and all, from the eldest down to the urchin of ten years old, who is reading his lesson, have the same grave, haughty, and even grim cast of countenance, which distinguishes the high feudal baron, their father. […] This picture... is one of the most celebrated monuments of art belonging to Scottish history, and cannot be looked on without awakening the most powerful recollection of those feudal times”.

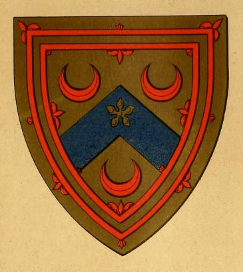

Arms of the Setons of Kylesmuir. John Seton, second son of William Seton of Kylesmuir, was described as “ane officer in France, wher the said John dyed.”

Illustration of the Eglinton estate from George Seton's History of the Family of Seton. The sixteenth century castle visited by Mary, Queen of Scots was replaced with the castellated mansion shown here by Hugh Montgomery, twelfth Earl of Eglinton, soon after his accession to the Earldom in 1796. In the Dining-room of the twelfth Earls' castle there hung a portrait of Mary Seton, one of the 'Four Marys'. A necklace gifted to Mary Seton by Mary, Queen of Scots was reputedly worn by the Countess of Eglinton.

Archibald Montgomerie, 13th Earl of Eglinton, acquired the Seton Earldom of Winton in 1859. George Seton, 5th Earl of Winton, had been stripped of the title for his adherence to the Jacobite cause in 1715. The historic importance of the Eglinton line of the Seton family is discussed in A history of the family of Seton during eight centuries by George Seton:

The importance of this distinguished branch of the family has been materially increased since it came to be regarded as inheriting the representation of the House of Seton, after the failure of the Kingston and Garleton branches in the male line. It must be borne in mind that, like several of the cadets who adopted other surnames, the Earls of Eglinton, since the beginning of the seventeenth century, though nominally Montgomeries, have been really Setons, and hence their claim to the headship of the great historic House of Seton.

Part IV - The Fullartons

The Fullarton family held lands in the western portion of Dundonald parish as vassals of the Stewarts. James Paterson in History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton states:

That part of the barony of Fullarton whence the family designation is derived, as also doubtless their surname, is situated in the immediate vicinity of the town of Irvine, upon the south-west side of the water of that name, and in the bailliwick of Kyle-Stewart, which is here separated from the district of Cuninghame.

The Fullarton place-name and surname is thought to derive from fowler-ton, the settlement or possession of the fowler, with the Fullarton family holding the hereditary office of fowler to the High Stewards of Scotland, later the Royal House of Stewart, whose local base was at Dundonald castle. In the role of fowler the Fullartons would have had the responsibility of providing the Stewarts with wildfowl such as ducks, geese and swans. James Paterson notes that the location of the castle of Fullarton was “peculiarly adapted for the pursuits of the fowler... being set down near the influx of the Irvine water into the sea, in the immediate neighbourhood of an extensive tract of low marshy lands, many hundreds of acres of which, at no distant period, were overflowed promiscuously with the waters of this river and the tides of the ocean... whilst the adjacent country was still thickly covered with natural wood”.

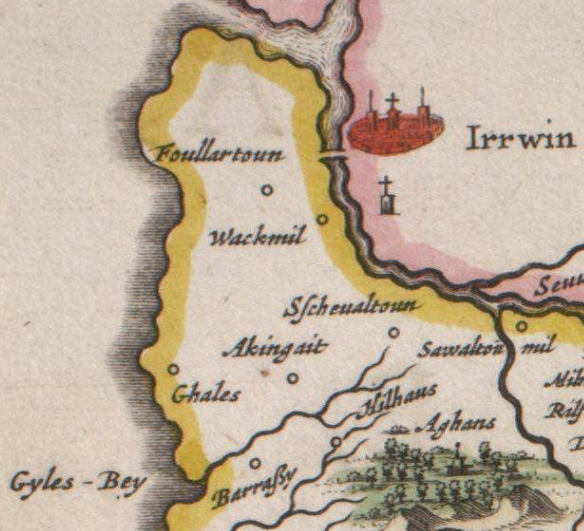

The Foullartoun lands, to the west and south of Irvine, depicted on the Blaeu Atlas of Scotland, 1654. (image source) Branches of the Fullarton family were also established in Kilmichael and Knightsland in Arran and 'Little Dreghorn', later known as Fairlie, in the eastern part of Dundonald parish.

Sir Adam Foullertoun, son of “Reginald Fowlertoun of that Ilk”, had a charter from Robert, High Steward of Scotland, of “the lands of Fowlertoun, and Gaylis [Gailes] in Kyle-Stewart, with the hail fishings from the Trune [Troon] to the water mouth of Irvine, and thence up the water (of Irvine) as far as the lands of Fowlertoun go ; and also an annual rent of four marks and a half out of the lands of Shewalton.” Sir Adam Fullarton fought in the army of king David II of Scotland at the Battle of Neville's Cross in 1346 where he was among a number of Scottish nobles captured and taken prisoner along with the king (other Ayrshire nobles captured during the battle include Thomas Boyd of Kilmarnock and Andrew Campbell of Loudoun). The Scottish invasion of northern England was launched after Philip VI of France appealed to David II to attack the English from the north in order to create a diversion. The French chronicler Jean Froissart described the Battle of Neville's Cross in his Chroniques :

On the morrow, the king of Scotland, with full forty thousand men, including all sorts, advanced within three short English miles of Newcastle, and took up his quarters on the land of the lord Neville. He sent to inform the army in the town, that, if they were willing to come forth, he would wait for them and give them battle. The barons and prelates of England sent for answer that they accepted his offer, and would risk their lives with the realm of their lord and king. They sallied out in number about twelve hundred men at arms, three thousand archers, and seven thousand other men, including the Welsh. The Scots posted themselves opposite to the English; and each army was drawn out in battle array.

[...]

The battle began about nine o’clock, and lasted until noon. The Scots had very hard and sharp axes, with which they dealt deadly blows; but at last the English gained the field, though it cost them dear by the loss of their men. On the part of the Scots, there fell in the field, the earl of Sys, the earl Dostre, the earl Patris, the earl of Furlant, the earl Dastredure, the earl of Mar, the earl John Douglass, sir Alexander Ramsay, who bore the king’s banners, and many other barons, knights, and squires. The king of Scotland was taken prisoner, fighting most gallantly, and badly wounded, before he was captured by a squire of Northumberland, named John Copeland, who, as soon as he got him, pushed through the crowd, and with eight other companions, rode off, and never stopped until he was distant from the field of battle about fifteen miles. He came about vespers to Ogle castle, on the river Blythe, and there declared that he would not surrender his prisoner, the king of Scotland, to man or woman except to his lord the king of England. That same day were taken prisoners, the earls of Murray and March, lord William Douglass, lord Robert de Wersy, the bishops of Aberdeen and St. Andrew’s, and many other barons and knights. There were about fifteen thousand slain, and the remainder saved themselves as well as they could. The battle was fought near Newcastle, in the year 1346, on a Saturday preceding Michaelmas day.

The Battle of Neville's Cross by the Dutch manuscript illuminator Loyset Liédet, from a 15th century manuscript of Froissart's Chronicles. (image source) Paterson notes that on king David's release eleven years later “the eldest son and heir of Sir Adam Fullarton was one of the twenty hostages left in England, until payment of the king's ransom. It is therefore probable that Sir Adam returned home at this time, if not sooner.”

The Fullartons in France

The Fullarton surname appears in the muster rolls of the Scottish Guard

under a number of variant spellings, including 'Folorton',

'Folourton', 'Felorton' and 'Foullarton'. Similarities can be seen with two of the alternative Scottish spellings of the name given by J.A. Balfour in The Book of Arran - 'Folartoun' and 'Foulartoune'. The spelling of 'Foullarton' in the muster rolls is identical

to one of the old Scots spellings of the name. Paterson mentions

“John Foullarton of that Ilk” who held the lands of Fullarton,

Troon and Crosbie in the late 15th century.

The surname first appears

in the Scots Guards muster rolls in 1480 when 'Jehan Folorton' is

listed among the 77 Archiers de la Garde. Jehan is a variant

of the French Jean (John). Jehan Folourton was a member of

the Guard in 1480-81 and 1484-1492. A certain Gilles or Giles

Folourton is recorded in the roll of 1483. Outside of the Scottish Guards, David Foularton was one of the hundred Scottish archers who fought in Charles VIII's Italian War of 1494-1498.

Within the ranks of the Scots Guards, Andre (Andrew) Folorton was a member of the Archiers de la Garde from 1518 until 1530 when he is listed among the senior Guardes de la Manche where he remained for the next fourteen years. A kinsman named 'Adam Fellorton' appears in the rolls of the Archiers de la Garde from 1535 to 1545 when he is listed among the Guardes de la Manche, apparently replacing Andre. This may be an example of a guardsman succeeding his father in a senior post.

Adam Fellorton remained a member of the senior archers of the Guard until 1559. Other members of the Fullarton or 'Follarton' family include 'Alexandre' (Alexander) Follarton, who served in the Guard from 1557 to 1563, Richard Follarton, 1561-63, and Jehan Foullarton, designated écuyer or esquire, 1572-78. After 1578 records of the Scots Guards are patchy, though there is a record of a 'Jehan Foularton' in 1587, with 'Anthoine Foularton' and 'Louis de Foullarton' listed among the senior guardsmen in 1624, 1632, 1640 and 1650. Louis de Foullarton was styled “Seigneur du Plessis, de Boinville, de Reignevillette et de la Pree en Gatinais”.

In History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton James Paterson mentions John Fullarton, second son of James Fullarton of Fullarton, who went to France in 1639 as lieutenant-colonel to Alexander Erskine, brother of the Earl of Mar. The following year he was made a colonel in the French army by king Louis XIII. Colonel Fullarton's Regiment, which comprised some 500-1000 men, was one of five Scottish regiments serving in France in 1642-43.

Part V - The Fergushills

The Fergushill family held the lands of Fergushill to the north of the Eglinton estate in the parish of Kilwinning. Of this estate and family, James Dobie, annotator of Pont's Cuninghame topographized, says:

This property, which, when entire, must have formed a valuable small estate, lies in the parish of Kilwinning. It belonged for several centuries to the Fergushills, who, probably, were vassals of the De Morevilles. The first notice which has been found of them is of Robert Fergushill de eodem, who is one of the Jury in the inquest at Irvine in 1417, before Robert, Duke of Albany, in the question between Francis of Stane and the Burgh.

The Fergushills of Fergushill were styled 'de eodem' or 'of that Ilk' meaning the surname was the same as the name of their estate. Robert and John Fergushill, along with John Montgomery, brother to Lord Montgomery, and John Montgomery of Giffen, are recorded as witnesses to the summons for high treason against John Ross of Montgreenan at the market cross of Irvine in 1488. In Cuningham topographized, written around 1604-1608, Timothy Pont records Fergushill as “Fergus-Hill ye habitatione of Robert Fergushill de eodem chieffe of hes name ane honest and descreit gentleman”. From this complimentary description it appears Pont had met the laird of Fergushill during his tour of the Cunninghame district. Fergushill appears on the 1654 Blaeu Atlas of Cunninghame as 'Feroushill'. This Atlas was based on maps drawn by Pont.

One member of the Fergushill family appears to have served in the Scottish Guard in France. 'Robin Fergousil' was a member of the Archiers de la Garde from 1458 to 1485. The surname is recorded under a variety of spellings including 'Fargozilles', 'Fergouzil' and 'Fargouzil'. Robin Fergousil may have been a son of the aforementioned Robert Fergushill of Fergushill (Robin was originally a diminutive form of Robert). Another possible member of the Fergushill family who served in France is 'Robert Fregouzel', listed alongside Georges de Montgomery in the 1550 muster roll of men-at-arms.

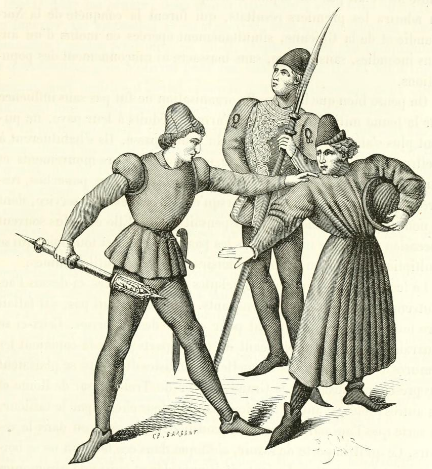

A mace bearer and royal guard controlling the crowd, from Jean Fouquet's Lit de justice de Vendôme, 1458 (pictured below), reproduced in Histoire du Costume, 1877, by Jean Quicherat. According to Quicherat the guards depicted by Jean Fouquet were those of the Scottish Guard but this is disputed by others who believe French guards are shown (see Forbes-Leith, The Scots Men-At-Arms and Life-Guards in France, vol 1 p137)

Lit de justice de Vendôme by Jean Fouquet. (image source) According to Stephen Wood, author The Auld Alliance, Scotland and France: The Military Connection, the guards in the foreground are Scots Guards armed with glaives.

Part VI - The Earls of Arran

The first of the Hamilton Earls of Arran was James Hamilton, son of James, Lord Hamilton, and Princess Mary Stewart of Scotland, eldest daughter of King James II. James Hamilton was made Earl of Arran with the seat of Brodick castle shortly after appearing at a tournament during the marriage of James IV of Scotland and Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII of England. In The Book of Arran (1910) author W.M. Mackenzie gives the following description of Hamilton's appearance at the tournament:

He was conspicuous in the affair of the marriage of James IV. with the Princess Margaret of England, showing gallantry at the ceremony on August 8, 1503, in a costume of white damask flowered with gold. Thus dazzling the Court, he, three short days thereafter, won the reward of merit, when the king, with consent of council and parliament, 'because of his nearness of blood, his services, and especially his labours and expenses at the time of the royal marriage in Holyrood,' conferred upon him 'the whole lands and Earldom of Arran, lying in the Sheriffdom of Bute'

The Earl is described in The Book of Arran as “a knightly man with his hands, a hero of tournaments, reputed the best archer on foot or on horse in Scotland, and a lover of horses”. In 1508 he took part in the tournament held in honour of the French embassy headed by Berault Stewart.

In 1513 the Earl of

Arran commanded a naval fleet with the intention of joining the

French in attacking the transports of Henry VIII sailing across the

Channel. The fleet, which consisted of around thirteen ships headed

by the Great

Michael, the

chief ship of the Scottish navy,

carried an armée de mer ('army

of the sea') of thousands

of troops. The Earl of Arran's fleet attacked the English stronghold

of Carrickfergus in Ulster before berthing at Ayr. Historian

Norman MacDougall suggests the fleet may have stopped

at Ayr to pick up recruits from families in the south-west of

Scotland who had relatives in France, such as the Stewarts, Montgomeries and Cunninghames.

Hamilton's fleet then headed for France but was hampered by bad

weather and the expedition was abandoned after the combined

Franco-Scottish fleet was scattered and the Great

Michael

ran aground. Of this venture Forbes-Leith remarks:

It does not appear that the troops under the command of the Earl of Arran acted with the French at the battle of the Spurs. As for the squadron, after a disastrous cruise on the coast of Ireland, its subsequent operations are involved in obscurity. We learn, however, that but few vessels returned to Scotland, and those in an unseaworthy condition.

The Earl of Arran appears to have remained in France until 1514 when he returned to Scotland to advance his career as a powerful noble with close ties to the Crown. He may have returned to France for a short period in 1520. His eldest son, James, succeeded to the Earldom of Arran while a younger son, John, became a monk at Kilwinning abbey. John Hamilton was appointed commendator of Paisley abbey at the age of fifteen, and after studying in Paris became Bishop of Dunkeld then Archbishop of St. Andrews.

James Hamilton, second Earl of Arran, accompanied James V to France in 1536 where the Scottish king married Madelaine, daughter of King Francis I of France. The Earl of Arran was later appointed regent to the young Mary, Queen of Scots, daughter and heir of James V, and negotiated her marriage to the Dauphin Francis, son and heir of King Henry II of France. Hamilton received the French duchy of Châtelherault for his role in arranging this union of the crowns of Scotland and France. He was also made a knight of the Order of Saint Michael. Forbes-Leith lists James Hamilton, second Earl of Arran, as a commander of men-at-arms in France in 1549.

The Earl of Arran's

half-brother, John Hamilton, the former monk of Kilwinning abbey who

became Archbishop of St Andrews, was a close adviser to the Earl.

Archbishop Hamilton was among the supporters of Mary, Queen of Scots

at the Battle of Langside in 1568.

Another kinsman, Gavin

Hamilton, fourth son of James Hamilton of Raploch, was also an

adviser to the Earl of Arran. Gavin Hamilton became Commendator of

Kilwinning abbey in 1550. Later that year, as one of the chief

advisers to the Regent Earl of Arran, he was sent for by Henry

II of France in order to discuss the king's proposals for the Earl's

resignation of the Regency. In 1552-53 he was again sent as

ambassador to the king of France. Gavin Hamilton remained

Commendator of Kilwinning abbey until his death in 1571. John

Anderson in

his Historical

and Genealogical Memoirs of the House of Hamilton (1825)

gives the following description of Gavin Hamilton:

He was a man of much spirit and ability, had great talents for business, and was well versed in all the learning of the times. He was in high favour with Queen Mary, to whose interest he ever continued attached.

Interestingly, the Earl of Arran's third son, John, Lord Hamilton, was Commendator of Arbroath abbey, a 'sister abbey' of Kilwinning, from 1551 to 1568.

In The Book of Carlaverock - Memoirs of the Maxwells, Earls of Nithsdale Sir William Fraser describes the arrival from France in 1569 of the Earl of Arran, here styled Duke of Chatelherault, accompanied by Gavin Hamilton, Commendator of Kilwinning:

On 17th February, the Duke of Chatelherault, (the next heir to the Crown of Scotland after King James the Sixth,) who had resided for some years in France, and who had been despatched by that Court to Scotland with the view of strengthening the interests of Queen Mary, arrived in Edinburgh from England. He had been detained for some months by Queen Elizabeth under various pretexts, but at last he was allowed by her to depart for Scotland.

Lord Herries and the Abbot of Kilwinning, who supported the claims of the Duke to the Regency in opposition to the Regent Murray, accompanied him to Scotland.

The Earl of Arran's eldest son, James Hamilton, succeeded to the Earldom in 1575. James Hamilton was in France from 1554 to 1559 where he commanded a company of men-at-arms. He was said to have been 'happiest on the battlefield' and was described by contemporary commentators as an excellent soldier. Brodick castle in Arran appears to have been a favoured residence of the third Earl until 1562 when he is said to have “showed signs of a disordered intellect”. A brief account of the third Earl's life is given by John Eaton Reid in History of the County of Bute and Families Connected Therewith (1864):

James, Third Earl of Arran, who aspired to the hand of Mary Queen of Scots, but the alliance was objected to, partly in consequence of their opposite views upon the subject of religion. Thereafter he became afflicted by mental incapacity, and was confined in Edinburgh castle for his eccentricities, but afterwards he was declared to be in a state of insanity, and was removed to his own castle of Hamilton, the Earls of Moray and Glencairn being surety that he would not pass beyond two miles around it. He died without issue in March, 1609, and was buried in the island of Arran, where he frequently resided.

Sculptured stone in Kilbride churchyard, Lamlash, Arran, depicted in The Book of Arran. This stone may have been the grave marker of the third Earl of Arran. The Book of Arran states, "It is difficult to know with certainty whose gravestone this is, but as James, third Earl of Arran, who died 1609, was buried in Arran, and there is no other site known as his resting-place, this stone may be associated with his name."

Part VII - The Earl of Irvine

In July 1572 Archibald Campbell, fifth Earl of Argyll, granted letters of protection to the Burgh of Irvine assuring the safeguard of the provost, bailies and community of the burgh. The letters describe this as a renewal of an "auld and ancient league" made in "times past the memory of man " between the Earl's predecessors and the burgh of Irvine. In the Royal Burgh of Irvine (1938) author Arnold McJannet states:

By the letters, Argyll received the community of the burgh into his protection, maintenance and safeguard, and bound himself in the defence of the freedom and liberty of the burgh, and its inhabitants in all their travels, suits, and lawful business, during his lifetime.

Interestingly, a kinsman of the Earl of Argyll, Hugh Campbell of Loudoun, was Provost of Irvine in 1572-73. He again held the post in 1574, 1579, 1582 and 1587. The Campbells of Loudoun were descended from Sir Donald Campbell, second son of Sir Colin More Campbell of Lochow, ancestor of the Argyll family.

In 1642 the fifth Earl of Argyll's grandson, James Campbell, received from King Charles I the titles of Earl of Irvine and Lord Lundy. James Campbell held the lands of Lorne in the west of Scotland. To this was added, in 1626, the lordship of Kintyre which consisted of practically the whole peninsula of Kintyre with the principal seat of Dunaverty castle, as well as the island of Jura in the Inner Hebrides. According to Arnold McJannet, it was probably in acknowledgement of the "ancient league" between the Campbells and Irvine that James Campbell "honoured the burgh by taking its name as his title" when he was made Earl of Irvine. In The History of Irvine - Royal Burgh and New Town historian John Strawhorn notes that Robert Barclay, Provost of Irvine, had been a tutor to James Campbell's brother, Archibald, future Marquess of Argyll, who was enrolled as an honorary burgess of Irvine in 1630.