The most ancient and the most famed ruins on this part of the coast were those of this castle of Robert Stuart, which bore the name of Dundonald Castle. At this period Dundonald Castle, a refuge for all the stray goblins of the country, was completely deserted. It stood on the top of a high rock, two miles from the town, and was seldom visited. Sometimes a few strangers took it into their heads to explore these old historical remains, but then they always went alone. The inhabitants of Irvine would not have taken them there at any price.

Jules Verne, The Underground City (1877)

Jules Verne and Scotland

Jules Verne (1828-1905), the celebrated “father of science fiction”, is best known for the novels Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, Around the World in Eighty Days and Journey to the Centre of the Earth. What is less well known is that Verne had a deep affinity for Scotland, and claimed Scottish ancestry. Verne's mother, Sophie, was apparently descended from a Scottish archer called N. Allotte, a member of the elite Scottish guard of king Louis XI of France, who reigned from 1461 to 1483. [1]

Jules Verne visited Scotland on at least three occasions. [2] These travels provided Verne with material for five novels and one novella set wholly or partly in Scotland. For example, Verne's third book Voyage à Reculons en Angleterre et l’Ecosse (published in English as Backwards to Britain) was closely based on his journey through England and Scotland in 1859.

Glasgow and the Firth of Clyde

The Glasgow - Firth of Clyde area features in five of Verne's novels – Backwards to Britain, The Blockade Runners, The Children of Captain Grant, The Underground City and The Green Ray. Glasgow was visited by Verne in 1859 and his time there is covered in Backwards to Britain. Verne arrived in Glasgow at Queen Street station and saw George Square, Kelvingrove Park, Glasgow Cathedral and the quays on the northern bank of the Clyde.

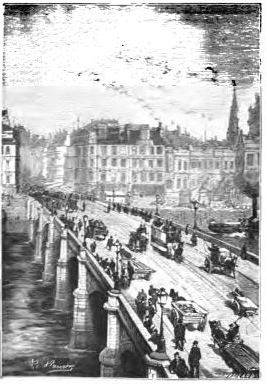

Drawing of Glasgow's Broomlielaw Bridge by Léon Benett from The Green Ray. This illustration appears on the cover of Backwards to Britain.

Verne's novella The Blockade Runners (1865), which begins and ends in Glasgow, has the following description of a ship, named the Dolphin, sailing through the Clyde area:

The descent of the Clyde was easily accomplished, one might almost say that this river had been made by the hand of man, and even by the hand of a master. For sixty years, thanks to the dredges and constant dragging, it has gained fifteen feet in depth, and its breadth has been tripled between the quays and the town. Soon the forests of masts and chimneys were lost in the smoke and fog; the noise of the foundry hammers and the hatchets of the timber-yards grew fainter in the distance. After the village of Partick had been passed the factories gave way to country houses and villas. The Dolphin, slackening her speed, sailed between the dykes which carry the river above the shores, and often through a very narrow channel, which, however, is only a small inconvenience for a navigable river, for, after all, depth is of more importance than width. The steamer, guided by one of those excellent pilots from the Irish sea, passed without hesitation between floating buoys, stone columns, and biggings, surmounted with lighthouses, which mark the entrance to the channel. Beyond the town of Renfrew, at the foot of Kilpatrick hills, the Clyde grew wider. Then came Bouling Bay, at the end of which opens the mouth of the canal which joints Edinburgh to Glasgow. Lastly, at the height of four hundred feet from the ground, was seen the outline of Dumbarton Castle, almost indiscernible through the mists, and soon the harbour-boats of Glasgow were rocked on the waves which the Dolphin caused. Some miles farther on Greenock, the birthplace of James Watt, was passed: the Dolphin now found herself at the mouth of the Clyde, and at the entrance of the gulf by which it empties its waters into the Northern Ocean. Here the first undulations of the sea were felt, and the steamer ranged along the picturesque coast of the Isle of Arran. At last the promontory of Cantyre, which runs out into the channel, was doubled; the Isle of Rattelin was hailed, the pilot returned by a shore-boat to his cutter, which was cruising in the open sea; the Dolphin, returning to her Captain’s authority, took a less frequented route round the north of Ireland, and soon, having lost sight of the last European land, found herself in the open ocean.

Jules Verne, The Blockade Runners, Chapter II - 'Getting Under Sail'

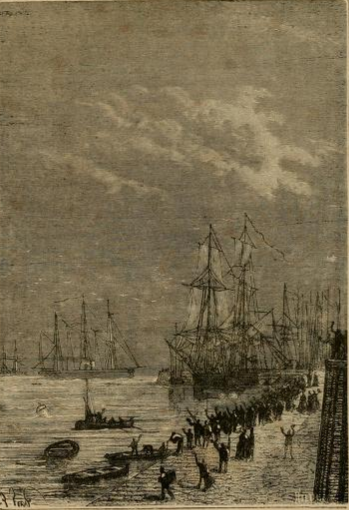

"The Dolphin trembled, passed between the ships in the port, and soon disappeared from the sight of the people, who shouted their last hurrahs." Launch of the Dolpin on the Clyde, illustration by Jules Férat from Les Forceurs de blocus (The Blockade Runners).

The Children of Captain Grant (1868)

opens

with a “magnificent yacht” sailing into the Firth of Clyde:

The DUNCAN was newly built, and had been making a trial trip a few miles outside the Firth of Clyde. She was returning to Glasgow, and the Isle of Arran already loomed in the distance, when the sailor on watch caught sight of an enormous fish sporting in the wake of the ship.

Jules Verne, The Children of Captain Grant (also known as In Search of the Castaways), Chapter 1

A detailed description of the Firth of Clyde and its islands, based on Verne's own observations of the area, can

be found in The

Green Ray (1882):

But

no matter, it was the sea which now lay before Helena's eyes. Through

the straits of the isles of Cumbrae, beyond the island of Bute,

softly outlined against the sky, beyond the crests of Ailsa Craig and

the hills of Arran, a clear line between sea and sky was distinctly

visible.

Jules Verne, The Green Ray, Chapter IV - 'Down the Clyde'

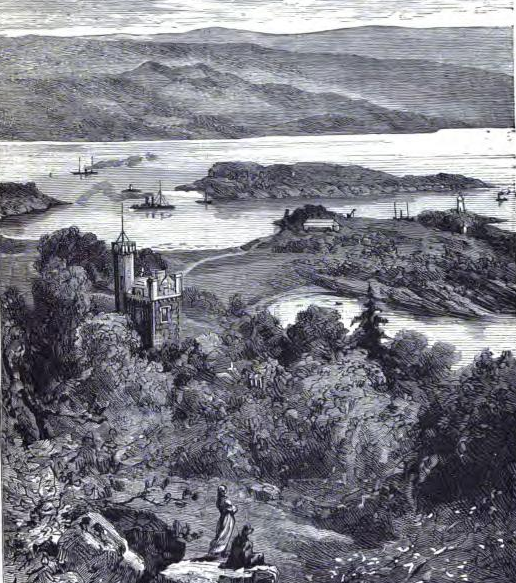

The Kyles of Bute. Illustration by Léon Benett from The Green Ray.

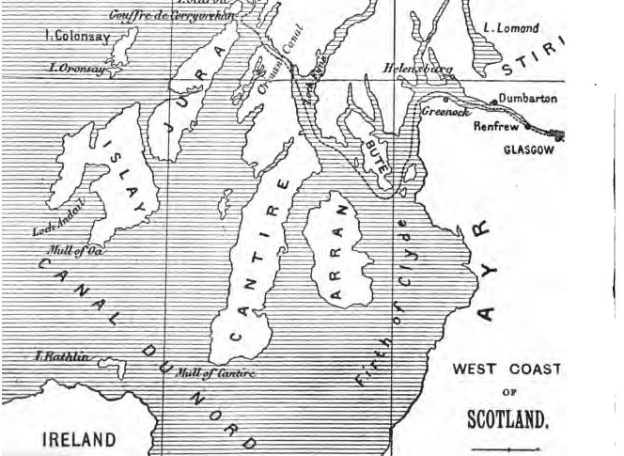

Map of the west coast of Scotland, from The Green Ray.

The itinerary of The Green Ray follows the route Verne took during his travels through Scotland in 1879, when he sailed round the northernmost part of the Firth of Clyde aboard the MacBrayne paddle steamer the RMS Columba. [3] The itinerary map from the original version of The Green Ray can be viewed here (for other maps in the Extraordinary Voyages series see Maps from the Extraordinary Voyages). The Green Ray is named after a phenomenon Verne introduced in The Underground City, “that ray of green which, morning or evening, is reflected upwards from the sea when the horizon is clear.”

The Underground City - Jules Verne and Ayrshire

Verne's novel Les Indes noires (The Back Indies) (1877), published in English as The Underground City, is set entirely in Scotland. This work, also published under the alternative title The Child of the Cavern; or Strange Doings Underground, was described by Michel Tournier of World Literature Today as “one of the strangest and most beautiful novels of the nineteenth century”. With its subterranean theme, The Underground City can be viewed as a 'follow up' to Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864). [4]

A

large part of the itinerary of The

Underground City follows

the Scottish leg of the Backwards

to Britain

journey

[5]. Edinburgh, Stirlingshire and the Trossachs form much of

the setting for Verne's novel.

Other

parts of the novel are set in Ayrshire, specifically Irvine and

Dundonald. This setting is a key part of the "plot within

a plot" of The

Underground City

[6].

Verne locates Irvine

and Dundonald at the southernmost limit of a massive cave system,

dubbed "New Aberfoyle", which extends from the Ayrshire

coast to the

Caledonian Canal in the Highlands.

We may easily imagine how soon this domain of New Aberfoyle became familiar to all the members of the Ford family, but more particularly to Harry. He learnt to know all its most secret ins and outs. He could even say what point of the surface corresponded with what point of the mine. He knew that above this seam lay the Firth of Clyde, that there extended Loch Lomond and Loch Katrine. Those columns supported a spur of the Grampian mountains. This vault served as a basement to Dumbarton. Above this large pond passed the Balloch railway. Here ended the Scottish coast. There began the sea, the tumult of which could be distinctly heard during the equinoctial gales. Harry would have been a first-rate guide to these natural catacombs, and all that Alpine guides do on their snowy peaks in daylight he could have done in the dark mine by the wonderful power of instinct.

Jules Verne, The Underground City, Chapter 10 - 'Coal Town'

The reason for Verne's inclusion of Irvine and Dundonald in The Underground City is something of a mystery. The location may have been chosen to give an idea of the scale of the vast New Aberfoyle mine. [7]

The

descriptions of Irvine and Dundonald in The Underground City may

have been based on first-hand observations of the area or information

gleaned from maps and guidebooks, or a combination of both.

Verne is known to have read the guidebook Promenade de Dieppe aux montagnes de'Ecosse (Promenade from Dieppe to the mountains of Scotland) (1821) by Charles Nodier. Verne praises Nodier and refers to this work in Backwards to Britain. Nodier's account of Kilmarnock, a neighbouring town of Irvine, may have prompted Verne to look more closely at the area. For more information on the connections between Nodier and Verne see 'Jules Verne and Charles Nodier', below.

Verne had studied Victor Adolphe Malte-Brun's map of Scotland prior to his 1859 visit. The Malte-Brun map, published in 1837, shows Irvine on the “Golfe de Clyde” (Firth of Clyde). [8] In The Underground City New Aberfoyle becomes a tourist attraction recommended by the “Joanne and Murray guidebooks”. This is a reference to the travel guides published by John Murray and Adolphe Joanne. Murray's Handbook for Travellers in Scotland (1875) covers Ayrshire, though it is doubtful if Verne could have used this as a source as there is no known French translation. [9]

Murray's Handbook for Travellers in Scotland describes Dundonald castle as “a mass of uncouth masonry, all the wrought stones having been taken out from the doorways and windows, and even the corners of the buildings carried away. The castle stands in a prominent position, occupying the whole summit of a hill. The dining-hall is entire, and the kitchen beneath is nearly so ; something is also left of the chapel above. Robert Stewart lived here before he came to the throne under the title of Robert II.” The next page in the guidebook contains the entry for Irvine, “another of the Ayrshire boroughs and ports, principally occupied in the shipment of coals. Population. 6866.” [10] (Verne gives a population of “about seven thousand inhabitants”).

Another guidebook, Black's Picturesque Tourist of Scotland (1852), describes the view of Dundonald castle under the heading 'Irvine':

After leavng Irvine, a view is obtained, on the left, of the remains of the ancient castle of Dundonald, standing on an elevated position, about two miles distant. The situation of this castle, on the top of a beautiful hill, is singularly noble. It was the property of Robert Stewart, who, in right of his mother, Marjory Bruce, succeeded to the Scottish throne under the title of Robert II.

The little port of Irvine is not much frequented, at least by vessels of large tonnage. It is rather more to the north that merchant vessels, sail or steam, pass on their way into the Firth of Clyde. [...] Its well-sheltered harbour has an important signal-light to indicate the reefs and banks, in such a way that a prudent sailor could never make a mistake. Wrecks were therefore rare on this part of the coast, and the coasters or cruisers wishing either to make for the Firth of Clyde, to get to Glasgow, or to bring up in Irvine Bay, could always manoeuvre without danger even in the darkest nights.

Verne's description of the "little sea-port" of Irvine from The Child of the Cavern (Sampson Low edition, 1877)

Sometime between 1868 and 1872 Jules Verne explored "the English coast and up the ocean to Scotland" in his yacht the Saint-Michel. This journey probably took him through the Irish Sea to the south-west coast of Scotland. [11] If the setting of parts of The Underground City in Irvine and Dundonald indicates that Verne visited the area he probably did so during this journey.

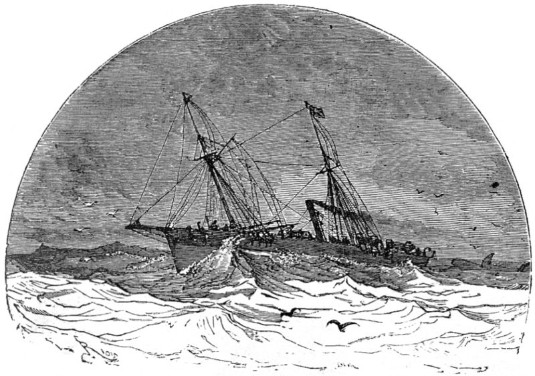

Verne's yacht, the Saint Michel, illustration from The Works of Jules Verne (1911)

Analysis of The Underground City is complicated by the fact that much of Verne's original manuscript was rewritten at the behest of his publisher, Pierre-Jules Hetzel. Verne originally envisaged an entire subterranean world below Scotland called “Underland” with a thriving city and surrounding settlements connected by rail, tram, steamboat and telegraph systems. This futuristic vision was, in Verne's own words, “completely demolished” by Hetzel.

The published version of The Underground City mentions the railway and station at Irvine. In

the original version Irvine, Glasgow and Stirling are connected by a

system of underground railways. [12] Verne had travelled to Glasgow via

Stirling during his tour of Scotland in 1859 and describes travelling through the long tunnel which leads to Glasgow Queen Street Station in Chapter 29 of Backwards to Britain, titled 'By train to Glasgow'. This chapter also refers to coal mines at Oakley and the use of coal in energy production.

During several days he had been engaged in exploring the remote galleries of the prodigious excavation towards the south. At last he scrambled with difficulty up a narrow passage which branched off through the upper rock. To his great astonishment, he suddenly found himself in the open air. The passage, after ascending obliquely to the surface of the ground, led out directly among the ruins of Dundonald Castle.

Jules Verne, The Underground City

It is difficult to know precisely how much of The Underground City is based, however loosely, on local facts and traditions which Verne may have picked up on his travels through Scotland. For example, the “Irvine games” or “merry-making” [13] could be based on the Irvine Marymass festival, though Verne's Irvine “festivities” are held on 12th December while the Marymass is held in August. Although the name “Melrose Farm” is unknown in the area, its location in the novel – on the coast with a view of Dundonald castle – matches that of Gailes farm to the south of Irvine. The tunnel leading to Dundonald castle is eerily reminiscent of local legends of underground tunnels connecting Dundonald castle to nearby Auchans castle [14] and the castles of Seagate and Stane in Irvine [15]. Such stories of secret tunnels are however fairly common throughout Britain.

Jules Verne and Edgar Allan Poe

Is all that we see or seem

But a dream within a dream?

Again and again I “dreamed that I was dreaming.” Now—this is an observation made by Edgar Poe—when one suspects that one is dreaming, the waking comes almost instantly.

Jules Verne, The Sphinx of the Ice Fields

Jules Verne was highly influenced by the works of Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849). In 1864 Verne wrote an article on Poe entitled Edgard Poë et ses oeuvres (Edgar Poe and his works) where he praised Poe as "the leader of the School of the Strange" [16]. In this he analyzed Poe's unfinished Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838):

Who will ever complete it? Surely someone more audacious than I and someone more willing to explore the realm of the impossible.

Verne's novel The Sphinx of the Ice Fields (1897) was in fact written as a sequel to the Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym. Poe's short story Three Sundays in a Week (1841) may have been the inspiration behind Verne's famous novel Around the World in Eighty Days (1873).

The cipher in Journey to the Centre of the Earth may have been based on Poe's cryptogram in The Gold Bug (1843). Other possible "borrowings" from Poe are mentioned by William Butcher in his introduction to Journey to the Centre of the Earth. [4]

Edgar Allan Poe in Scotland

Hervey Allen, Israfel, The Life and Times of Edger Allan Poe Vol I (1927)

After the death of his mother, the young Edgar Poe was taken into the home of John Allan, a Scottish merchant in Virginia who came from Irvine. In 1815 Poe was brought to Irvine to live with John Allan's uncle William Galt (a distant relative of the novelist John Galt) [17] This period of Poe's life is mentioned by Jules Verne in his article on Poe, Edgard Poë et ses oeuvres [18]:

Un

monsieur Allan, négociant à Baltimore, adopta le jeune Edgard, et

le fit voyager en Angleterre, en Irlande, en Ecosse

Considering Verne's admiration for Edgar Allan Poe and knowledge of his time in Scotland could he have set part of The Underground City in Irvine as a tribute to Poe?

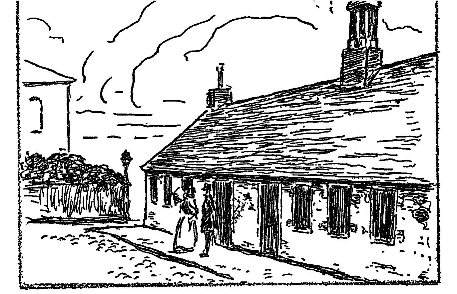

The grammar school, located in the Kirkgate of Irvine, which Poe attended in 1815. From Israfel, The Life and Times of Edgar Allan Poe, by Hervey Allen.

Hervey Allen - Israfel, The Life and Times of Edger Allan Poe Vol I

Extracts from The Underground City, Chapter IX, 'The Fire-Maidens'

...several legends were based on the story of certain “fire-maidens,” who haunted the old castle. The most superstitious declared they had seen these fantastic creatures with their own eyes. Jack Ryan was naturally one of them. It was a fact that from time to time long flames appeared, sometimes on a broken piece of wall, sometimes on the summit of the tower which was the highest point of Dundonald Castle.

- ...

- ...the day after the Irvine games, Jack Ryan intended to take the railway from Glasgow and go to the Dochart pit; and this he would have done had he not been detained by an accident which nearly cost him his life. Something which occurred on the night of the 12th of December was of a nature to support the opinions of all partisans of the supernatural, and there were many at Melrose Farm.

- ...

He now had his back to the sea. His companions turned also, and gazed at a spot situated about half a mile inland. It was Dundonald Castle. A long flame twisted and bent under the gale, on the summit of the old tower.

“The Fire-Maiden!” cried the superstitious men in terror.

Clearly, it needed a good strong imagination to find any human likeness in that flame. Waving in the wind like a luminous flag, it seemed sometimes to fly round the tower, as if it was just going out, and a moment after it was seen again dancing on its blue point.

All was then explained. The ship, having lost her reckoning in the fog, had taken this flame on the top of Dundonald Castle for the Irvine light. She thought herself at the entrance of the Firth, ten miles to the north, when she was really running on a shore which offered no refuge.

What could be done to save her, if there was still time? It was too late. A frightful crash was heard above the tumult of the elements. The vessel had struck. The white line of surf was broken for an instant; she heeled over on her side and lay among the rocks.

...

The ship was the Norwegian brig Motala, laden with timber, and bound for Glasgow. Of the Motala herself nothing remained but a few spars, washed up by the waves, and dashed among the rocks on the beach.

Jules Verne, The Underground City, Chapter IX 'The Fire-Maidens'

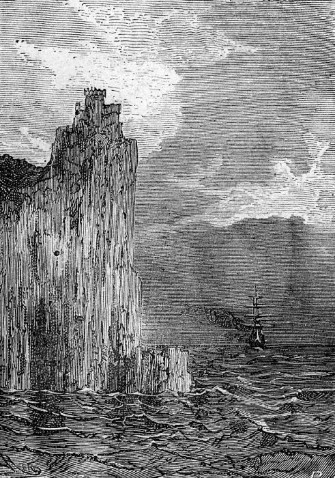

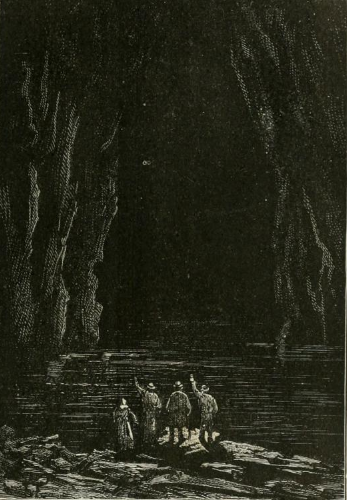

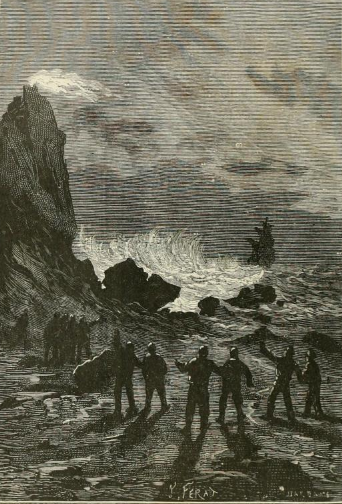

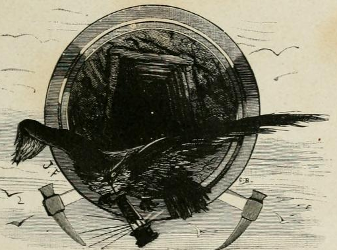

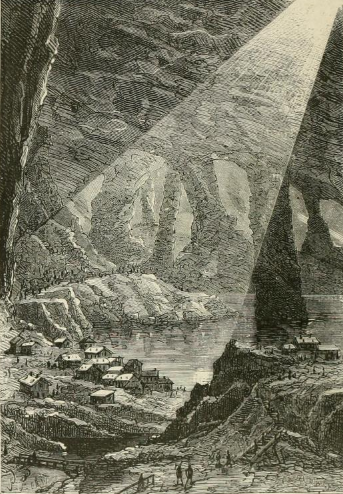

The fire-maidens of Dundonald castle by Jules Férat from Les Indes Noires. This illustration bears little resemblance to the actual situation of Dundonald castle and in fact deviates from Verne's narrative where Jack Ryan is described facing inland towards the castle with "his back to the sea".

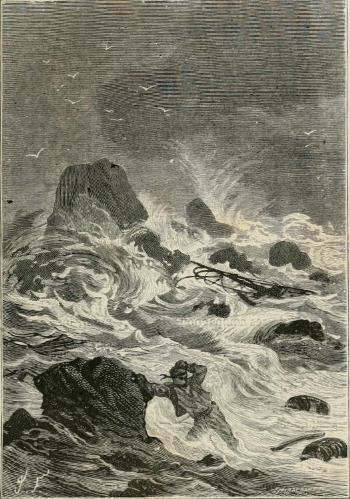

Illustration by Jules Férat from Les Indes Noires showing the destruction of the Motala. Motala is the name of a town in Sweden visited by Verne during a tour of Scandinavia in 1861. [19] In Verne's novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea (1870) the prow of the submarine Nautilus was built at Motala. [20]

Jules Verne and Sir Walter Scott

The

writings of Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) are known to have been a major influence on

Jules Verne. In an interview with Marie A. Belloc in 1895 Verne

stated “All my life I have delighted in the works of Sir Walter

Scott , and during a never-to-be-forgotten tour in the British Isles,

my happiest days were spent in Scotland. I still see, as

in a vision, beautiful, picturesque Edinburgh, with its Heart of

Midlothian, and many entrancing memories; the Highlands, world-forgotten

Iona, and the wild Hebrides. Of course, to one familiar with the works of

Scott, there is scarce a district of his native land lacking some

association connected with the writer and his immortal work.” [21]

Scott and Ayrshire

Ayrshire's associations with Scott can be found in Old Mortality (1816), set in south-west Scotland during the time of the Covenanters. The aforementioned Murray's Handbook for Travellers in Scotland, in its entry for Kilwinning, the neighbouring town of Irvine, states, "Kilwinning was noted for the excellence of its archers ; and the shooting of the popinjay as detailed in "Old Mortality", used, until late years to be the annual custom here. The Kilwinning Company of Archers, as it is called, claims an antiquity of about 400 years." Groome's Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland (1882) states, "Every person acquainted with Sir Walter Scott's novels, will recognise the Kilwinning festival, transferred to a different arena, in the opening scene of Old Mortality, when young Milnwood achieves the honours of Captain of the Popinjay, and becomes bound to do the honours of the Howff."

Loudoun Hill, a volcanic plug near the source of the River Irvine, is mentioned a number of times in Scott's Old Mortality:

Where are these knaves?" he continued, addressing Lord Evandale. "About ten miles off among the mountains, at a place called Loudon-hill," was the young nobleman's reply.

...

Numbers of these men, therefore,

took up arms; and, in the phrase of their time and party, prepared to

cast in their lot with the victors of Loudon-hill.

This name may have intrigued Verne, whose Scottish ancestor had established a seat, the Chateau de la Fuye, at Loudun, in western France.

Verne may have read Scott's Tales of a Grandfather and History of Scotland which contain several references to Irvine and Dundonald. These include an account of the fight between William Wallace and several English soldiers near the River Irvine and a passage dealing with the 'Auld Alliance' between Scotland and France and the death of king Robert II at Dundonald.

In

the summer of the same year, 1389, a truce of three years was formed

betwixt France and England, in which Scotland was included as the ally

of the former power. Shortly after this event, king Robert II died at

his castle of Dundonald in Ayrshire. He was at the advanced age of

seventy five, and had reigned nineteen years.

Walter Scott, The History of Scotland (1830)

The Underground City and Scott

The Underground City contains many references to Scott and his works, with one of the principal characters, James Starr, described as “a great fan of Walter Scott, as is every true son of Caledonia”. A key moment in The Underground City is the sunrise viewed from the summit of Arthur's Seat. While waiting for the sunrise James Starr quotes from The Heart of Midlothian by Scott:

If I were to choose a spot from which the rising or setting sun could be seen to the greatest possible advantage, it would be that wild path winding around the foot of the high belt of semicircular rocks, called Salisbury Crags, and marking the verge of the steep descent which slopes down into the glen on the south-eastern side of the city of Edinburgh.

The Salisbury Crags are a series of cliffs adjoining Athur's Seat. When the sun rises in Verne's novel the light causes the pinnacle of the Scott Monument to glow like a lighthouse. In Backwards to Britain

Verne gives a detailed description of the Scott Monument in Edinburgh

with its statues of Walter Scott, the Lady of the Lake and the Last

Minstrel.

Verne places "Coal City", the "underground city" of the title, below Loch Katrine, the lake in Scott's Lady of the Lake. This poem, with its "Coir-nan-Uriskin" or "Goblin's Cave" on the shore of Loch Katrine, is a possible source for the 'supernatural' elements in Verne's story. [22]

Verne may have derived the names of the “Yarrow Shaft” and “Melrose Farm” from Scott's narrative poem The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805), which mentions the Yarrow river and Melrose abbey as part of the setting in Scott's favourite “wild Border country”. The supernatural elements of The Lay of the Last Minstrel involve the recovery of a magic book from the tomb of the wizard Michael Scott at Melrose abbey and a goblin or “elfish dwarf” who attaches himself to the recoverer of the book. [23]

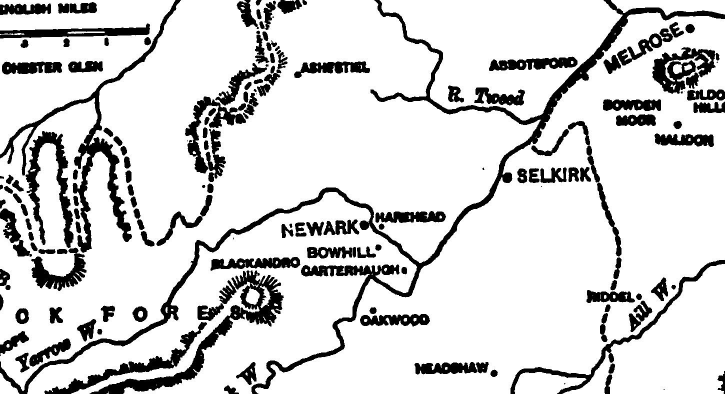

Map

showing the location of Melrose (top right) and the Yarrow water

(bottom left). Abbotsford House, near Melrose, was the residence of

Walter Scott. Map source

Ian Thompson, in his introduction to The Underground City, describes Verne's story as one of opposites, of good and evil, light and dark, rational and supernatural etc. [24] The character of Jack Ryan who, at the beginning of the novel, works and lives at Melrose Farm, is a key figure in the 'supernatural' element of the story :

In the first rank of the believers in the supernatural in the Dochart pit figured Jack Ryan, Harry's friend. He was the great partisan of all these superstitions. All these wild stories were turned by him into songs, which earned him great applause in the winter evenings.

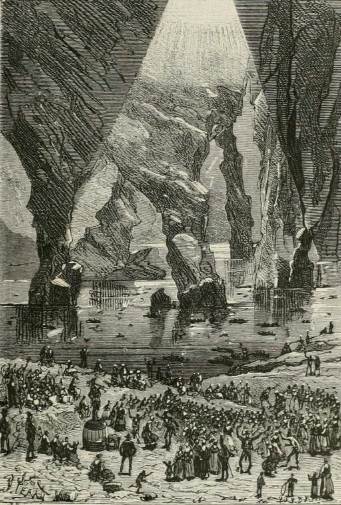

Crowds dance as Jack Ryan plays the bagpipes in this illustration from Les Indes Noires by Jules Férat. Verne scholar Ian Thompson has described Jack Ryan as "a unique creation in Verne's Scottish stories". [25]

Jack Ryan, as a musician, singer, poet and storyteller, can be seen as a kind of 'minstrel' figure. His belief in the supernatural leads him to view any unexplained phenomena as the work of nebulous spirits or goblins :

A goblin, a brownie, a fairy's child," repeated Jack Ryan, "a cousin of the Fire-Maidens, an Urisk, whatever you like! It's not the less certain that without it we should never have found our way into the gallery, from which you could not get out.

It is from Melrose Farm that Jack Ryan witnesses the “fire-maidens” of Dundonald castle. Verne's description of this spectacle has striking similarities with Scott's “beacon-blaze of war” in The Lay of the Last Minstrel :

A long flame twisted and bent under the gale, on the

summit of the old tower.

...

Waving in the wind like a luminous flag, it seemed sometimes to fly round the tower, as if it was just going out, and a moment after it was seen again dancing on its blue point.

Jules Verne, The Underground City

For a sheet of flame from the turret high

Waved like a blood red flag in the sky,

All

flaring and uneven

Walter Scott, The Lay of the Last Minstrel

The "fire-maidens" of Dundonald castle may also be a form of word-play based on an old name for Edinburgh castle. In Backwards to Britain Verne recounts how Edinburgh castle was known as 'Maidens Castle' or Castrum Puellarum "in the time of the minstrel-kings". Edinburgh castle is briefly mentioned towards the end of The Underground City.

Jules Verne and Charles Nodier

Another significant influence on the Scottish novels of Jules Verne was the French author and poet Charles Nodier. Backwards to Britain opens with a quote from Les Marionnettes, a short story by Nodier. Verne made extensive use of Nodier's Promenade from Dieppe to the mountains of Scotland with 'borrowed' elements appearing in Backwards to Britain and The Underground City. [26] Nodier's account of Kilmarnock in Promenade may have influenced Verne in setting part of The Underground City in the neighbouring town of Irvine.

Professor Ian Thompson has identified Nodier's

eerie descriptions of large birds near Loch Kathrine in Promenade

as a possible source for the "monstrous

owl"

in The

Underground City

[27] (pictured above, from the title page of Les

Indes Noires).

Eager to approach my object, eager perhaps to get away from the sinister aspects of these nameless deserts, I took advantage of the long glimmering of the crepuscular light to get over the greatest space possible, before dark came on entirely; and I walked, or rather fled, attended by the screams of a great white bird, whose solitary covey I had probably disturbed, and which pursued me for five or six miles with its frightful cries, like those of a sick child.

Charles Nodier, Promenade from Dieppe to the mountains of Scotland, Chapter XXV, 'From Ben Lomond to Loch Kathrine'

...towards midnight I heard the branches of a fir creak under the weight of a powerful animal, whose vigorous wings beat through the foliage and the air. It was a great owl, traversing the air, and holding in his beak either a snake or an eel

Charles Nodier, Promenade from Dieppe to the mountains of Scotland, Chapter XXVII

Scott, Nodier and The Underground City

Verne's description of Dundonald castle as the refuge of “stray goblins” or “wandering imps” may have been influenced by Scott's Lay of the Last Minstrel and Nodier's Trilby, ou le lutin d'Argail (Trilby, or the fairy of Argyll) (1822). Both of these works feature an exiled or wandering goblin or imp as a main character. Nodier's Trilby has been noted as a possible source of inspiration for The Underground City [28]. Much of the geographical setting of Trilby, which ranges from the Trossachs to the “Bay of Clyde”, appears in The Underground City. Parallels can also be drawn between the fictitious 'Balvaig monastery' in Trilby and Verne's depiction of Dundonald castle in The Underground City - both are ruinous towers standing on the summit of rocky hills, both are surrounded by an aura of superstition, and both are the haunt of stray supernatural beings. In his preface to Trilby Nodier states, “the subject of this story is derived from a preface or a note to one of the romances of Sir Walter Scott, I do not know which one.” According to Georg Brandes in Main Currents In Nineteenth Century Literature the story of Trilby was based on a legend told to Nodier by Amedee Pichot, the French translator of Scott.

Scott's Lay of the Last Minstrel features a goblin who is “lost” or “strayed”, which is based on the folktale of 'Gilpin Horner'.

The young Countess of Dalkeith, wife of the heir apparent to the headship of the clan Scott, had heard the legend of Gilpin Horner – a strange tricksy goblin who appeared among the Borderers in the shape of an ugly little dwarf, and had a habit when excited of muttering 'Tint! Tint! Tint!' (Lost! Lost! Lost!) as if it had strayed away from its supernatural master into human society. The Countess suggested to Scott that he should write a ballad about it.

Walter Scott, Lay of the Last Minstrel, Editor's Preface (1886)

Scott explained the origins of the poem in a letter of 1805:

The story of Gilpin Horner was told by an old gentleman to Lady Dalkeith, and she, much diverted with his actually believing so grotesque a tale, insisted that I should make it into a Border Ballad. I don’t know if ever you saw my lovely chieftainess—if you have, you must be aware that it is impossible for any one to refuse her request, as she has more of the angel in face and temper than any one alive; so that if she had asked me to write a ballad on a broomstick, I must have attempted it. I began a few verses, to be called The Goblin Page; and they lay long by me, till the applause of some friends whose judgment I valued induced me to resume the poem; so on I wrote, knowing no more than the man in the moon how I was to end. At length the story appeared so uncouth, that I was fain to put it into the mouth of my old Minstrel—lest the nature of it should be misunderstood, and I should be suspected of setting up a new school of poetry, instead of a feeble attempt to imitate the old.

Cassilis Downans

Upon that night, when fairies light

On Cassilis Downans dance,

Or owre the lays, in splendid blaze,

On sprightly coursers prance;

Or for Colean the rout is ta'en,

Beneath the moon's pale beams;

There, up the Cove, to stray an' rove,

Amang the rocks and streams

To sport that night;

The poem is set in Burns' native Ayrshire. "Cassilis Downans" was, according to Burns, the name of "certain little, romantic, rocky, green hills, in the neighbourhood of the ancient seat of the Earls of Cassilis". This seat is Cassilis House, located on the banks of the River Doon, in Ayrshire. The Cove at "Colean" is a reference to the Culzean Coves, a series of caves dug into the rock below Culzean castle. According to Burns these caves and the "Cassilis Downans" were "famed, in country story, for being a favourite haunt of fairies."

The Underground City and Journey to the Centre of the Earth

Let us cut our trenches under the waters of the sea! Let us bore the bed of the Atlantic like a strainer; let us with our picks join our brethren of the United States through the subsoil of the ocean! Let us dig into the centre of the globe if necessary, to tear out the last scrap of coal.

Jules Verne, The Underground City

Verne scholar William Butcher has described The Underground City as a 'follow up' to Journey to the Centre of the Earth. [4]

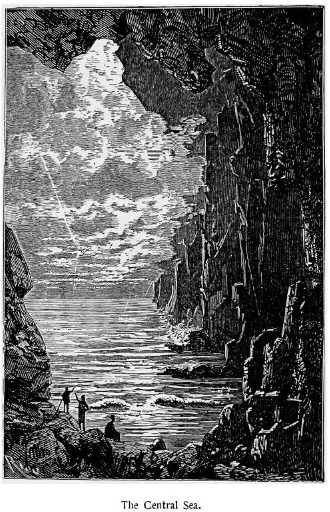

In Journey to the Centre of the Earth Verne places the shore of the "Lidenbrock Sea" below Scotland :

"Have you any idea of the depth we have reached?"

"We are now," continued the Professor, "exactly thirty-five leagues—above a hundred miles—down into the interior of the earth."

"So," said I, after measuring the distance on the map, "we are now beneath the Scottish Highlands, and have over our heads the lofty Grampian Hills."

In The Underground City the "Yarrow Shaft", the entrance to the vast caverns of New Aberfoyle, is described as resembling an extinct volcano, an echo of the dormant volcano which leads to the earth's interior in Journey to the Centre of the Earth :

They

walked into the shed which covered the opening of the Yarrow shaft,

whence ladders still gave access to the lower galleries of the pit.

The engineer bent over the opening. Formerly from this place could be

heard the powerful whistle of the air inhaled by the ventilators. It

was now a silent abyss. It was like being at the mouth of some

extinct volcano.

Verne describes New Aberfoyle as comparable to “the famous Mammoth Cave in Kentucky”, the longest known cave system in the world :

…

Below the dome lay a lake of an extent to be compared to the Dead Sea of the Mammoth caves—a deep lake whose transparent waters swarmed with eyeless fish, and to which the engineer gave the name of Loch Malcolm.

The Mammoth Cave is also used as a comparison in Journey to the Centre of the Earth. In both works caverns and tunnels are described in architectural terms. In The Underground City one of the tunnels at the bottom of the Yarrow Shaft resembled "the nave of a cathedral” while another tunnel "was like a nave, the roof of which rested on woodwork, covered with white moss." New Aberfoyle is described as a "labyrinth of galleries, some higher than the most lofty cathedrals, others like cloisters, narrow and winding". In Journey to the Centre of the Earth there is a "succession of arches... like the aisles of a Gothic cathedral."

1. William Butcher, Jules Verne - The Definitive Biography, 8

2. William Butcher and Sarah Crozier, Verne's Underground City, the Lost Chapters from Les Indes noires, 1

3. Jules Verne, The Green Ray, Afterword by Professor Ian Thompson 218-221 ; William Butcher, Jules Verne, The Definitive Biography 262-263

4. Jules Verne, Journey to the

Centre of the Earth,

Introduction by William Butcher

5. Ian B. Thompson, Jules Verne, Geography and Nineteenth Century Scotland

6. Ian Thompson, Jules Verne's Scotland - In Fact and Fiction 134

7. E-mail communication from Professor Ian Thompson 11 October 2011

8. Jules Verne, Backwards to Britain, 3, 75

9. William Butcher and Sarah Crozier, Verne's Underground City, the Lost Chapters from Les Indes noires 11

10. Murray's Handbook for travellers in Scotland, 120-121

11. William Butcher, Jules Verne, The Definitive Biography 229 William Butcher and Sarah Crozier, Verne's Underground City, the Lost Chapters from Les Indes noires 2

12. William

Butcher and Sarah Crozier, Verne's Underground City, the Lost

Chapters from Les Indes noires 12

13. Jules Verne, The Underground City, A new translation. In the translation by Sarah Crozier "Irvine clan festival" and "Irvine festival" replaces "Irvine games" and "Irvine merry-making".

14. For the supposed tunnel between Dundonald castle and Auchans see the entry in Wikipedia for Auchans castle.

15. The story of a tunnel at Stanecastle may have some basis in fact. A subterranean passage or vault was discovered by workman making the turnpike road. CANMORE site record for Stane Castle, Subterranean Structure A "Subterranean Passage" is shown on the first edition Ordnance Survey map (1856).

16. Arthur B. Evans, Literary Intertexts in Jules Verne's Voyages Extraordinaires

17. John Strawhorn, History of Irvine, 93, 101 ; BBC Radio Scotland - Scots Gothic – A Portrait Of Edgar Allan Poe In Ayrshire

18. Jules Verne, Edgard Poe et ses œuvres This can be read in English via Google translate

19. Jules Verne, Joyous Miseries of Three Travellers in Scandinavia, Translated with an introduction, notes and appendices by William Butcher, page 31

20. Jules Verne, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea, A new translation by William Butcher, 87. The book can be read online. In the online version the reference to Motala appears on page 98.

21. Marie A. Belloc, Jules Verne at Home, Strand Magazine, February 1895. "His library is strictly, for use, not show, and well-worn copies of such intellectual friends as Homer, Virgil, Montaigne, and Shakespeare, shabby, but how dear to their owner; editions of Fenimore Cooper, Dickens, and Scott show hard and constant usage"

22. Sir Walter Scott, The Lady of the lake, 176 http://www2.hn.psu.edu/faculty/jmanis/w-scott/lady-lake.pdf

23. Sir Walter Scott, The Lay of the Last Minstrel at the Walter Scott Archive

24. Jules Verne, The Underground City, foreword by Professor Ian Thompson xiv

25. Ian Thompson, Jules Verne's Scotland - In Fact and Fiction 136

26. Ian Thompson, Jules Verne's Scotland - In Fact and Fiction 29, 54, 90 ; Jules Verne, Backwards to Britain 89, 141 ; Ian Thompson, 'Re: A possible origin for the harfang in Les Indes noires', Jules Verne Forum

27. Ian Thompson, Jules Verne's Scotland - In Fact and Fiction 155 ; 'A possible origin for the harfang in Les Indes noires', Jules Verne Forum

28. Ian Thompson, Jules Verne's Scotland – In Fact and Fiction 90 ; Jules Verne, Backwards to Britain, Afterword by Christian Robin 214

Sources and further reading

Allen, Hervey. Israfel, The Life and Times of Edger Allan Poe, 1926

Belloc, Marie A. Jules Verne at Home, Strand Magazine, 1895Butcher, William. Jules Verne: The Definitive Biography. Thunder's Mouth Press, 2006.

Butcher, William and Crozier, Sarah. Verne's Underground City, The Lost Chapters from Les Indes noires. www.ibiblio.org/julesverne/articles/undergroundcity.doc

Evans, Arthur B. Literary Intertexts in Jules Verne's Voyages Extraordinaires

Nodier, Charles. Promenade from Dieppe to the mountains of Scotland 1822

Nodier, Charles. "Smarra" & "Trilby" Dedalus European Classics 1993

Scott, Walter. The Lay of the Last Minstrel. Fredonia Books, 2002. Reprinted from the 1895 edition.

Strawhorn, John. The History of Irvine, Royal Burgh and New Town. 1985.

Thompson, Ian Jules Verne's Scotland: In Fact and Fiction Luath Press, 2011

Thompson, Ian B. Jules Verne, Geography and Nineteenth Century Scotland

Verne, Jules. Backwards to Britain. Translated by Janice Valls-Russell. Chambers, 1992.

Verne, Jules. Edgard

Poe et ses œuvres.

Verne, Jules. In Search of the Castaways; or the Children of Captain Grant at Project Gutenberg

Verne, Jules. The Green Ray, A new translation, translated by Karen Loukes. Luath Press, 2009.

Verne, Jules. The Underground City, A new translation, translated by Sarah Crozier. Luath Press, 2005.

Verne, Jules. The Underground City, or, the Child of the Cavern at Project Gutenberg.

Interview with Ian Thompson, Verne scholar

Literary Scotland: A Traveller’s Guide mentions Verne's travels in Scotland and his three Scottish novels.

How Scotland inspired Jules Verne

Rediscovered: Jules Verne's lost Scotland

Jules Verne's 'lost' novel reveals Scottish inspiration for father of science fiction

20,000 Leagues Below Loch Katrine has an interview with translator Sarah Crozier

Journey to the Centre of... Fife

Text, excluding quotes and extracts, copyright © John Loney

Photograph of Jules Verne from Wikipedia

Photographs of Dundonald castle copyright © John Loney