James IV, the Auld Alliance and the Battle of Flodden

On the 10th of December 1502, standing at the right hand of the high altar of Glasgow Cathedral, King James IV of Scotland ratified the 'Treaty of Perpetual Peace' between England and Scotland. The treaty had been concluded at the beginning of the year in London by a Scottish embassy led by Robert Blacader, Archbishop of Glasgow. At the altar of Glasgow Cathedral, in the presence of two envoys of Henry VII of England, James IV “swore on the sacraments to observe the treaties of peace and marriage concluded by his ambassadors on 24th January preceding”.

As part of the treaty a marriage was arranged between James IV and Margaret Tudor, eldest daughter of Henry VII. The marriage took place at Holyrood on the 8th of August 1503 and was a lavish affair with festivities spread over the following five days.

Portrait of James IV and Margaret Tudor from the Seton Armorial (1591).

Despite the 'Treaty of Perpetual Peace' Anglo-Scottish relations worsened over the following ten years while the 'Auld Alliance' between Scotland and France became stronger. From 1502 James IV built up his naval forces with French assistance, with shipwrights and timber brought over from France. James offered the services of the Scottish fleet to king Louis XII of France in a letter dated August 1506. [James IV p232-233, 242-243] In July 1504 James IV purchased or hired a French barque, named the Colomb, which was subsequently based at Dumbarton.

Historian Norman MacDougall describes the construction of the royal navy as king James' “obsession”. Vast sums of money were poured into the project which involved the construction of two new dockyards in the Firth of Forth. In the west shipbuilding work was carried out at Ayr, Glasgow and Dumbarton. In May 1512 a galley was under construction at Glasgow and in July of that year there is record of another galley being built at Ayr. The Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland lists a payment to “Johne Broun of Air, in part of payment for the biggein of ane new galay to the King in Air”.

A wooden keel was brought from France for the ship known as the Margaret, built in a specially constructed dock in Leith and launched in June 1506. The Margaret, named after king James' wife, Margaret Tudor, was comparable in size to the English Mary Rose, launched three years later.

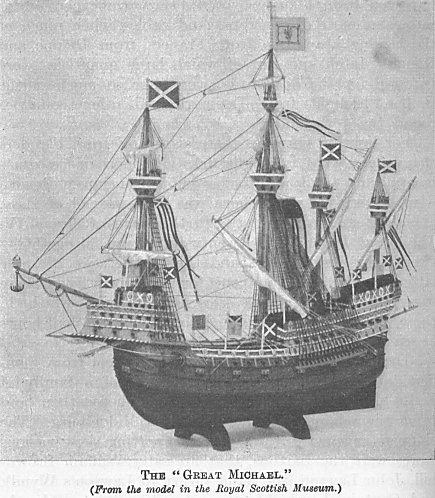

The Margaret was superseded in size by the Michael, popularly known as the Great Michael, launched to great fanfare at Newhaven on October 1511. The Michael, described in the accounts as “the gret schip”, had a crew of three hundred and carried twenty-seven large cannon. According to the 16th century chronicler Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie the woods of Fife were “wasted” to provide timber for the construction of the Michael:

the king of Scottland bigit ane great scheip callit the great Michell quhilk was the greattest scheip and maist of strength that ewer saillit in Ingland or France. For this scheip was of so greit statur and tuik so mekill timber that scho waistit all the wodis in Fyfe except Falkland wode, by (besides) all the tymmer that was gottin out of Noraway.

Based on the reports of Charles de Toque, the French ambassador to Scotland who had been received aboard the Michael by James IV on 30 November 1512, king Louis XII of France declared the ship to be the greatest in Christendom.

As well as building new royal ships king James hired a number of smaller privately owned vessels. Peter Foulartoun was captain of Chalmer's barque which appears to have belonged to Thomas Chalmers. Chalmer's barque carried sixty men, mostly fighting men rather than sailors. Peter Foulartoun may, presumably, have been related to the Fullarton family of Fullarton, near Irvine.

The 16th century Scottish historian George Buchanan gives the following account of the ships commissioned by James IV, focussing on the magnitude of the Great Michael :

...he expended great sums in beautifying the palaces at Stirling, Falkland, and other royal residences, besides erecting several monasteries. His greatest extravagance, however, was shipbuilding. He constructed three vessels of very large bulk, besides others of smaller dimensions ; but one far exceeded in size, cost, and equipment, any ship that had ever been seen upon the ocean. Besides the descriptions of this vessel given by our historians, and her dimensions preserved in some places, this sufficiently indicates her magnitude : - That when Francis, king of France, and Henry VIII., king of England, stimulated by emulation, endeavoured to outvie her, and built each a vessel a little larger, they, after being finished and fully equipped, when launched, were immoveable from their magnitude, and unfit for any useful purpose.

James IV and Irvine

James IV visited Irvine in 1506, 1507 and 1512. The weathered stone in the west wall of Irvine parish church carved with the initials 'MQ' and the date '1506' (pictured below) is said to commemorate the visit of James IV and Queen Margaret in 1506 during a pilgrimage to Whithorn. [1]

On the 8th of August 1511 James IV issued a charter ratifying all previous grants to the burgh of Irvine addressing “our well-beloved the bailies and community of our burgh of Irvine... for their good and thankful service done to us”.

Less than a year later James IV made an expedition to Ayrshire. During this trip, which lasted at least eleven days, the king visited Ayr (where he purchased a cloak and plaid), Irvine, Ailsa Craig and “St. Mary Isle”, which is probably another name for the Lady Isle near Troon. The king's baggage, which included crossbows and gunpowder, was carried by six horses. In his preface to volume 4 of the Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland Sir James Balfour Paul states:

Whether this expedition was of a warlike nature, perhaps connected with an attack by the cruisers of the English King on a French vessel which ran in for protection to an anchorage off the coast of Ayr, or whether it was merely a sporting excursion to shoot sea-fowl on Ailsa Craig, is not clear. Perhaps it was not of either character, but connected with some communication to the Duke of Albany, as on the 30th of April “Monsieur de Albanies Secretar” was given £36 “as his passage to France”. This took place on the coast of Ayr, as we read of a payment to the men of Irvine that brought the King in a boat to land.

This was the king's last visit to Irvine.

Renewal of the Auld Alliance

In 1511 king Henry VIII of England joined the so-called 'Holy League' against France which consisted of Pope Julius II, Venice, Ferdinand of Spain and Emperor Maximilian. This forced James IV to choose between the 'Perpetual Peace' with England and the 'Auld Alliance' with France. He chose the latter, renewing the Auld Alliance in March 1512 after months of negotiations with the French.

This renewal of the Franco-Scottish alliance led to James IV launching a land and sea campaign against England the following year in response to Henry VIII's invasion of France. In July 1513 James IV dispatched a naval fleet with the intention of joining the French in attacking the transports of Henry VIII sailing across the Channel. The king appointed his cousin James Hamilton, first Earl of Arran, admiral of the fleet. Hamilton had been granted the Earldom of Arran with the seat of Brodick castle shortly after appearing at a tournament during the marriage of James IV and Margaret Tudor.

The fleet which Arran commanded consisted of the royal ships – including the capital ships, the Michael and the Margaret – accompanied by privately owned vessels, including Chalmer's barque captained by Peter Foulartoun, and several foreign barques. The fleet numbered around thirteen large vessels and carried an armée de mer ('army of the sea') of thousands of troops. According to Scottish historian Patrick Tytler there were “thirteen great ships... besides ten smaller vessels”. Tytler puts the strength of the army on board at three thousand.

The king had a new gold coin struck, possibly to mark the occasion and with great expectations for his fleet. The coin depicts the archangel Michael defeating the dragon and a ship with three masts bearing the arms of Scotland, perhaps to represent the warship, the 'Great Michael'. The legend on the coin reads “Salvator in Hoc Signo Vicisti” - “Saviour in this sign hast thou conquered”

© The Trustees of the British Museum (source)

The fleet set sail in the last week of July and headed north, avoiding the English ships which patrolled the east coast of England. James IV remained on board the Michael until they reached the Isle of May in the outer Firth of Forth. Thereafter the fleet appears to have followed a circuitous course through the Pentland Firth and Hebrides before attacking the English stronghold of Carrickfergus in Ulster. After looting Carrickfergus the Earl of Arran's fleet returned to Scotland, berthing at the port of Ayr. These events are described by the 16th century Scottish historian George Buchanan in his History of Scotland :

James, king of Scotland, although he had determined to remain neuter, yet being inclined to favour his ancient ally, resolved to send the fleet, formerly mentioned, as a gift to the French queen, Anne, that it might appear rather as a pledge of friendship, than any assistance for carrying on the war.

...having heard that great preparations were making for a maritime war, James determined to send the fleet, we have mentioned, to Anne immediately, that it might, if possible, arrive there before the war broke out. He appointed James Hamilton, earl of Arran, admiral, and ordered him to sail with the first fair wind ; but Hamilton, a simple kind of man, more acquainted with the arts of peace than of war, either afraid of danger, or through his natural indolence, having delayed to go to France, landed at Carrick-Fergus, a town in Ireland, opposite Galloway, and after pillaging the place, burned it, and set sail for Ayr, a harbour of Kyle in Scotland, as if he had performed a great exploit.

Rather than being a sign of “indolence” the Earl of Arran's attack on the English stronghold at Carrickfergus may have been carried out as part of the alliance formed between James IV and Hugh O'Donnell of Ulster. The Annals of Ulster record how O'Donnell “went, [with] small force, to Scotland, at invitation by letters of the king of Scotland, when he received great honour and donatives from the king.” The alliance between James IV and Hugh O'Donnell was made on the 25th of June 1513. The Archbishop of Glasgow, and the Earls of Arran, Eglinton and Glencairn were among the nineteen Scottish witnesses to the agreement. [2]

Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie describes how the Earl of Arran's fleet “passit to the wast sie wpoun the cost of Ireland and thair landit and brunt Carag-forgus witht wither willagis, and than come foranent the toune of Air and thair landit and repossit and playit them the space of xl [forty] dayis.”

While berthed at Ayr the fleet was no doubt resupplied with victuals and ammunition. Given it's proximity to Ayr, the port of Irvine may also have had a role in supplying the Earl of Arran's fleet. In 1514 the Crown required the burgh of Irvine to provide vessels and mariners for the expedition against the Lord of the Isles. As John Strawhorn points out in his History of Irvine, the burgh of Irvine is likely to have made similar provisions on earlier occasions.

Historian Norman MacDougall suggests the Earl of Arran's fleet may have stopped at Ayr to pick up recruits from families in the south-west of Scotland who had relatives in France. [3] The Stewart, Montgomery and Cunninghame families were prominent in France, most notably in the Garde Écossaise, or Scottish guard, the elite bodyguard of the French kings. The Scottish guard in 1513 was captained by Robert Stewart, son of Sir John Stewart of Darnley. The Stewarts of Darnley held significant tracts of land in Ayrshire including Dreghorn, Galston and Tarbolton. Members of the Fullarton family also served in the Scottish guard during the 15th and 16th centuries. The surname appears in the muster rolls of the Guard under a variety of spellings, including 'Folorton', 'Folourton' and 'Foullarton'.

Less than a month after the royal fleet left the Firth of Forth under the command of the Earl of Arran, king James IV led a massive invasion of north-east England. The prime military objective of the campaign, the taking of Norham castle, was achieved within a week. In early September the Scottish army moved south, capturing the smaller castles of Etal and Ford before encamping on the summit of Flodden Hill where they faced the army of the Earl of Surrey.

The invasion achieved the wider objective of drawing English forces from northern France. The Earl of Surrey was joined by his son, Lord Thomas Howard, who had returned from France with a force of a thousand men, according to the 16th century Chronicle of Edward Hall. Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie gives a higher figure, narrating how James IV invaded England “for lufe of France” prompting Henry VIII to despatch six thousand of his best men from France to England.

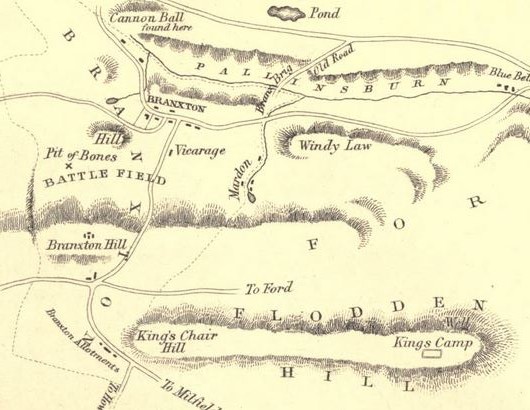

On the 9th of September the Scots moved from the summit of

Flodden Hill towards the nearby Branxton Hill in an attempt to deny

the English the high ground. The Earl of Surrey had manoeuvred his

forces to the foot of Branxton Hill, blocking a northwards retreat

back to Scotland and forcing the Scots to fight.

'Map of Flodden Field And its Vicinity' by Rev. R. Jones, from Archaeologia aeliana, or, Miscellaneous tracts relating to antiquity (1822)

While the two huge armies were roughly the same size – about 20,000 men in each – the Scots suffered a terrible defeat. Buchanan gives an estimate the number of Scots killed:

Many noblemen fell in the king's division. They who reckon the number of the slain, by the number of individuals taken from each parish, make the amount of the Scots, who were slain in this battle, above five thousand

By the end of the battle king James IV lay dead on the field along with a considerable portion of the Scottish nobility including nine earls and fourteen lords of parliament. Those from Ayrshire included David Kennedy, first Earl of Cassillis, Thomas Boswell of Auchinleck, Robert Cunninghame of Cunninghamehead [4], Cuthbert Montgomery of Skelmorlie [5] and George Campbell of Cessnock.

David Kennedy, Earl of Cassillis, was related to the Montgomeries of Eglinton through his mother, Lady Elizabeth Montgomerie. George Campbell of Cessnock was son-in-law of the Earl of Eglinton. The Scots Peerage records that “on 7 November 1513 Hew, Earl of Eglintoun, was surety for his daughter Jonet, Lady of Cessnock, that the goods and gear of her husband should be forthcoming to her son and other heirs.”

William Bunche, Abbot of Kilwinning, is listed among the Scottish dead in the contemporary 'Trewe encountre or batayle lately don betwene Englande and Scotlande' where he is recorded as the “abbot of Kilwenny”. There is however serious doubt surrounding the abbot's supposed presence and death at Flodden. [6]

Alexander Johnston, burgess of Ayr, and John Elphinstone, burgess of Glasgow, were among the dead, as were burgesses from Dundee and Edinburgh. If representatives of Irvine burgh were present at Flodden, which seems likely, it appears they were among the survivors. Historian Norman MacDougall notes that retention of contingents from royal burghs may have been easier due to guaranteed payment for the full forty days military service.

Aftermath

The maritime fleet commanded by the Earl of Arran arrived in France in mid-September after being delayed by a storm, described by the chronicler Robert Lindsay as “the storme of windis and raige of sieis”. Arran's fleet then joined up with a French naval force under the command of Louis de Rouville. This Franco-Scottish fleet became scattered by another storm and the Michael ran aground. The plan to attack the transport ships of Henry VIII was abandoned. In The Scots Men-At-Arms and Life-Guards in France (1882) historian William Forbes-Leith states:

It does not appear that the troops under the command of the Earl of Arran acted with the French at the battle of the Spurs. As for the squadron, after a disastrous cruise on the coast of Ireland, its subsequent operations are involved in obscurity. We learn, however, that but few vessels returned to Scotland, and those in an unseaworthy condition.

This assessment by Forbes-Leith is based, at least in part, on the earlier History of Scotland by Patrick Fraser Tytler. In volume 5 of The history of Scotland (1866) Tytler provides what he describes as “unsatisfying conjectures” regarding the fate of the Earl of Arran's fleet after it had left Ayr:

Over the future history of an armament which was the boast of the sovereign, and whose equipment had cost the country an immense sum for those times, there rests a deep obscurity. That it reached France is certain, and it is equally clear that only a few ships ever returned to Scotland. Of its exploits nothing has been recorded - a strong presumptive proof that Arran's future conduct in no way redeemed the folly of his commencement. The war, indeed, between Henry and Lewis was so soon concluded that little time was given for naval enterprise; and the solitary engagement by which it was distinguished, (the battle of Spurs,) appears to have been fought before the Scottish forces could join the French army. With regard to the final fate of the squadron, the probability seems to be that, after the defeat at Flodden, part, including the Great Michael, were purchased by the French government; part arrived in a shattered and disabled state in Scotland; whilst others which had been fitted out by merchant adventurers, and were only commissioned by the government, pursued their private courses, and are lost sight of in the public transactions of the times.

At least some of the Scottish soldiers of the 'armee de mer' had returned home by mid-November, a number of whom claimed to have been ill-treated by the French. The Earl of Arran appears to have remained in France until 1514 when he returned to Scotland to advance his career as a powerful noble with close ties to the Crown.

The defeat at Flodden led to strife in parts of Ayrshire. According to Chalmer's Caledonia (1824) “many violent acts were committed in Scotland, particularly in the south” including the seizing of the castles of Ochiltree and Cumnock, whose owners had died at Flodden.

Chamber's Gazetter of Scotland (1836) further states:

The fatal battle of Flodden was disastrous to Ayr and the adjacent country. Some of the best nobles in the shire were slain, with the provost of the town and the flower of the inhabitants. Such losses were rendered more unfortunate by the criminal ambition of many surviving families of rank, who violently took possession of the property of their deceased neighbours, and it was with difficulty that the privy council dislodged them.

Norman MacDougall, James IV p266-67, 279

Norman MacDougall, An Antidote to the English, The Auld Alliance, 1295-1560 p117

William Emond, The minority of King James V, 1513-1528, Appendix A: The Flodden Death-Roll

William Fraser, Memorials of the Montgomeries, Earls of Eglinton Volume I, p155

Jim Kennedy, The Abbey of Kilwinning (part 23 – The Last Real Abbot) ; Sister Dominic Savio, Kilwinning Abbey p10

Sources:

Bain, Joseph (ed.) Calendar of documents relating to Scotland preserved in Her Majesty's Public Record Office, London Volume IV (1888)

Buchanan, George. The History of Scotland Translated from the Latin of George Buchanan. Volume II 1827.

Chalmers, George. Caledonia 1824

Chambers, Robert. The gazetteer of Scotland 1836

Emond, William K., The minority of King James V, 1513-1528 Ph.D., St. Andrews University, 1988

Forbes-Leith, William. The Scots Men-At-Arms and Life-Guards in France 1882 Nabu Public Domain Reprint

Hall, Edward. Chronicle. ed. Henry Ellis. London, 1809.

Laing, David (ed.) A Contemporary Account Of The Battle Of Floddon, 9th September 1513 Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Vol. 7 1867.

Lindsay, Robert. The Historie and Cronicles of Scotland : From the Slauchter of King James the First to the Ane Thousande fyve hundreith thrie scoir fyftein zeir William Blackwood & Sons 1899

MacCarthy, Bartholomew (ed.) Annals of Ulster Volume III

MacDougall, Norman. An Antidote to the English: The Auld Alliance, 1295-1560 Tuckwell Press, 2001

MacDougall, Norman. James IV John Donald Publishers 2006

Nicholson, Ranald. Scotland: The Later Middle Ages. The Edinburgh History of Scotland. Volume 2. 1974

Paul, James Balfour (ed.) Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, Volume IV. 1877

Strawhorn, John. The History of Irvine, Royal Burgh and New Town 1985

Thorburn, William Stewart. A guide to the coins of Great Britain & Ireland 1888

Tytler, Patrick Fraser. The history of Scotland from the accession of Alexander III. to the union 1866

Muniments of the Royal Burgh of Irvine Volume 1 Published by the Ayrshire & Galloway Archaeological Association 1890

Text, excluding quotes and extracts, copyright © John Loney

johnloney93@yahoo.co.uk

Portrait of James IV from Wikipedia.